As I stopped to listen to the various stories and history of Transylvania their magic came to me from prehistory to Roman Dacia, through writings and oral traditions, artefacts and ruins. Like a weave of strands of various origin, those of the many European nations whose genetic melting pot boiled down to one population, the Romanian. I sit now under the stars, half way between Orient and Occident, and separate strands so I can tell their stories further.

Yet this green highland and animal heaven hides haunted tombs, caves, and unbelievable riches (salt, copper, gold, silver), fascinating fortresses, and up to this day, a maze of forests. The eagle’s cry speaks of secrets and a faith worth dying for, that of the peasant who caressed the land with his hand, or of the warrior who shed his blood for it. It sings of emotions turned to feelings, feelings that bled into battles.

In Stories and History of Transylvania, Prehistory to Roman Dacia you can read (among other) about:

- The Paleolithic Civilization of Transylvania Painted Horses on Cave Walls

- What are the Paleolithic horse paintings of Transylvania telling us

- How were the cave paintings done?

- A Paleolithic Skull in Transylvania

- Neolithic Transylvania Sees a Great Human Migration

- The boulder head on a Neolithic grave from Gura Baciului, Cluj county, Transylvania, Precriş culture

- The Gigantic Neolithic Fortress of Turdaș, Hunedoara, Transylvania

- Transylvania during the Bronze Age (3200 / 2700 – 1100)

- The Transylvanian Horses of the Bronze Age

- The “Birth of the Metal” in Transylvania and its Symbolism

- Transylvania from the Iron Age to Roman Dacia (1 100 BC – 150 AD)

- What is the Etymology of word Dac? From Warrior Nickname to Ethnic Identity

- Celtic Tribes visit Transylvania IV – II BC

- Dacian Gold Kingly Helmet of Coțofenești, Prahova County, Romania 400BC

- Dacians and Dacia under King Burebista

- Deceneu, the great King of Dacians from Transylvania

- Dacians under Burebista and the Silent Temple of Sarmizegetusa

- The Legacy of the Dacian Civilization

- groups of young men who had to prove themselves able to survive outside their community while hide and live from their prey.

- immigrants in search of a new territory to settle or outlaws, fugitives looking for a sheltered land, as the wolf was the symbol of the fugitive and the gods protecting them also had names deriving from wolf.

Romulus and Remus, the legendary founders of Rome city, were sons of wolf-god Mars, fed by a she-wolf, (lupa in Latin, lup in Romanian) on the banks of Tiber river, on the site of future Rome. The twins became leaders of a band of adventurous youths. - ritualistic ability to turn into a wolf, especially by wearing the skin of one – as performed during military initiations, as a true warrior was expected to be as fearless as a wild animal. Also, by wearing the skin of a wolf the warrior would leave behind any human traits, such as the fear of going into battle, fear to be killed, inability to kill other humans. Or wearing the skin of a wolf reinforced the belief that after death the warrior will be reborn as a fearless, enlightened animal.

- belief in reincarnation, metensomatosis;

- belief that the soul survives after death in a happy place;

- belief that life is worse than death, although the soul is mortal, which explains why Getae warriors were not afraid of death.

Stories and History of Transylvania, the Icy Prehistory

The Paleolithic Civilization of Transylvania Painted Horses on Cave Walls

Theirs was a time when gleaming glaciers still covered the earth. During the coldest period all of Scandinavia and most of Germany and Poland were locked beneath a silent ice sheet. Ice covered Scotland and most of Ireland. Europe’s shoreline spread farther than we know it today, that even England joined France. The life belt for animals and the first modern people of Europe was the region at the south, between southern England to Russia

But even here, snow fell until late June – even today, every Romanian knows that before July 1st the mighty Transfagarasan mountain road might still be closed due to snow. Silent starry nights often transformed dew into ice crystals and as early as October pristine blankets of snow lay across the green land – today, mid-October is the time that still signals the closing of the Transfagarasan road through the Carpathians due to snowfalls.

January’s howling winds and swirling storms drove herds of game – bison, horses, deer, wolves, wild boar, foxes – towards the protected valleys, for warmth and food. And man followed. On foot and claded in fur, muscular, skilled men followed quietly. Ready for ambush as food was scarce.

Artwork reveals the diversity and sophistication of ancient people, even if it was realized 100 000 years ago and is shrouded in time’s forgotten cycles. I wonder how much different the artist who painted the caves of Transylvania really was in comparison to Banksy? The Paleolithic artist, too, used their intellectual capacity and creativity which they adapted to their time and place. They, too, pondered over human problems and they, too, had hopes and aspirations.

Civilizations that developed in Transylvania are as old as the Paleolithic era (100,000 BC) and they left cultural vestiges behind, such as the cave paintings of horse from Cuciulat near Someș river, Sălaj district, in north-west of Transylvania.

What are the Paleolithic horse paintings of Transylvania telling us

The cave paintings dating from Paleolithic tell us that Transylvania’s civilization was one of hunters, the men surely fishing too in the abundant rivers nearby, during short summer months. They had weapons, while women would most probably look after their tiny family and gather fruits, wild plants, leading a life in tee-pees sheltered in caves. Their was a life led in small groups. Food was scarce and it had to be followed, ambushed, killed, winter time or not.

And we can also tell that horses were abundant and important, seen perhaps as a food source (their meat), shelter and clothes (their skin and hair), tools, even weapons (their bones).

How were the cave paintings done?

You see the hand print above? The cave painter would have blown powdered pigment through a tube (a hollow stick or reed) to leave an outlined hand-print. A signature or simply a marking of his presence. For colors, he would have used minerals, ochres (earth pigments), burnt bone meal and charcoal mixed into water, blood, even animal fats and tree saps to etch his artwork depicting humans, animals and symbols.

You see the weapons? See the humans ambush the horses?

What was the purpose of the cave art? Was it hunting magic? To keep the herds nearby? Were they meant for fertility or for art’s sake? Or just stress relieve? Visual clues for storytelling?

Were the cave paintings made out of basic human drive towards art and aesthetics, a drive to be surrounded by beauty?

Whatever the reason for cave painting, the prehistoric man of Transylvania depicted life symbols flourishing under the power of the sun, and chose to do so in one of the darkest spot underground, a cave, as if he wished to bring and lock inside it the everlasting sunlight and its life-giving powers.

A Paleolithic Skull in Transylvania

When the 33 000 years old fossilized skull of a Paleolithic adult man, known as the Cioclovina calvaria (a calvaria is a skullcap), shows up in a cave in south-west Transylvania, at Cioclovina, south of Hunedoara (and Corvin Castle) and the skull even displays clear signs of trauma, a scenario worthy of Bones comes to my mind.

What was he doing in this cave? Had he followed some game while other hunters followed him? Or had he stumbled onto a different group’s cave and he was outnumbered? Had he dies engulfed by darkness or by the light of a life giving fire, surrounded by his small family?

Skipping forward through time, I’ll only mention that tools made of flint and obsidian as well as artifacts dating to the Tardenoisian culture of the Mesolithic period were found in south-east Transylvania – an important finding as similar cultures were known as far as France and Belgium.

The end of this period marked the end of the last Ice Age, which resulted in the extinction of many large mammals and, as glaciers began to recede in Europe, sea levels rose and climate warmed up, a change that eventually caused man himself to migrate, learn the rudiments of agriculture and turn from watchful hunter to settled farmer.

Neolithic Transylvania Sees a Great Human Migration

It appears that the Neolithic population of South Balkan area migrated northwards, bringing their advanced agricultural skills along, such as crop production, animal breeding and mingling, settling among the local groups (Tardenoisian period).

Archeological sites from Gura Baciului (Cluj county, Transylvania), a Precriş culture, and from Ocna Sibiului (Sibiu county, Transylvania) and their findings tell the story of a Neolithic civilization that lived in underground shelters as well as in homes raised on river stones. Their pottery has geometrical patterns and they created the first clay statuettes. They either bury their dead or incinerate them.

The boulder head on a Neolithic grave from Gura Baciului, Cluj county, Transylvania, Precriş culture

When they buried the dead, which they loved and mourned, to honor him and keep him safe from scavengers, they laid him to rest on the floor of the home they shared together. Great care was then taken in the search of an oval shaped boulder in which two eyes and a mouth were carved. The boulder was placed facing west and near the head of the deceased, so that each morning when the sun’s blessed light enters through the open door, the face carved on the boulder is brought to life. Then, and only then, the deceased’s body was incinerated and the family deserted their home.

At Gura Baciului and westwards there is a hill, perhaps the equivalent of the mountain guarding Netherworld.

Starčevo-Criş culture in the Intra-Carpathian territory (Transylvania)

Perhaps a continuation of the Gura Baciului-Precriş culture, the Neolithic Starčevo-Criş culture of Transylvania left us beautiful burned pottery, the first small copper items and dwellings placed wherever the landscape permitted.

The Neolithic Vinca – Turdaș culture painted wheat on pottery

A new wave of migrations from Balkan Peninsula brings to Transylvania the polished black pottery and the Vinča culture, named Vinča – Turdaș in Transylvania due to its strong local influences (the Starčevo-Criş traditions) such as the clay used for pottery making and the small altars with feet:

The Gigantic Neolithic Fortress of Turdaș, Hunedoara, Transylvania

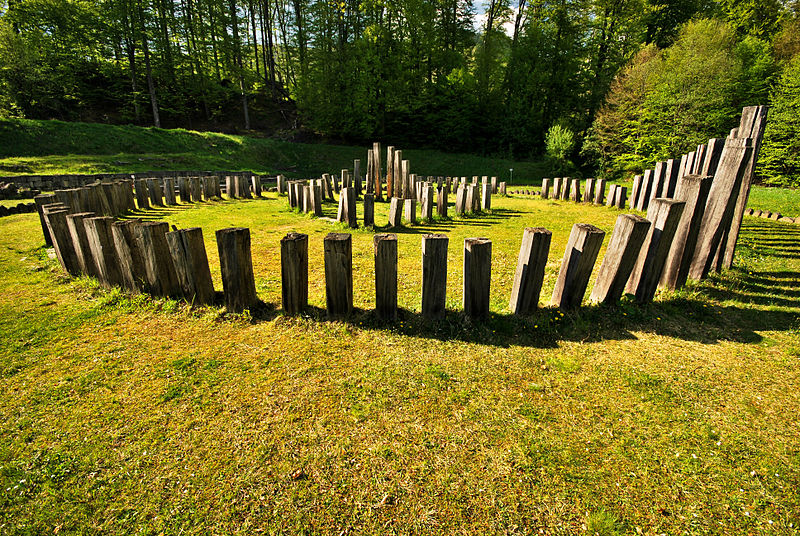

Discovered only in 2013 during work on a local national road, the only gigantic Neolithic fortress of Turdaș culture was built near Mureș river (easy to travel on) in 4 200 BC, covering 100 hectares, and was raised 1 600 years before the Pyramids of Egypt. This city-fortress had 1 300m of fortifications and 6 – 7 km of fortified wood walls built of spikes, with defense towers and entrance gates. Inside, this city fortress had roads, houses and even neighborhoods.

Archeological findings tell of human sacrifices performed as rituals so the fortress will thrive and stay protected.

Proof that the fortress was a spiritual center is shown by the many statues depicting deities. Many of these statues are identical, suggesting local manufacturing after which the statues were transported outside the walls, perhaps to other spiritual centers.

Pottery was thriving, with over 60 ovens discovered, and weaving was also developed as well as manufacturing of copper tools. (Image source Malus Dacus).

The Vinča – Turdaș culture was a Neolithic archaeological culture in southeastern Europe, present-day Serbia, parts of Bulgaria, Macedonia and Romania (particularly Transylvania, but also Oltenia, Banat, Moldavia, west of Muntenia, and north of Moldova), dating to 5700–4500.

The existence of mining areas in Transylvania at this time confirms the local population’s metallurgical knowledge of copper, gold, tin and iron.

The pottery discovered here had painting of wheat on it, proving that agriculture was also developed. Zigzag and spiral patterns symbolize moving waters feeding the earth, while the astral bodies painted on pottery prove human’s connection with the spiritual forces, all created by the Transylvanian populace.

A new addition, the homes are now fortified.

The Turdaș culture was build on a hierarchy ruled by a king, while the Cucuteni (located in northwest Romania towards the north) knew an agricultural, matriarchal and peaceful lifestyle.

Could this Turdaș culture mark the place of the first ever kingdom in the history of the world? The Egyptian culture existed only later, during 3 000BC.

It could be, as the statues belonging to this culture depict men siting on a throne, a symbol of royalty:

What is sure is that the archeological site of Turdas fortress is the wealthiest site in Europe.

Worth mentioning and remembering is that all the future cultures in the Carpathian-Danube space (excluding Hamangia) draw their roots from the Vinča – Turdaș culture.

It is believed by some historians (Marija Gimbutas) that the rich valley of Danube river (marking today’s south border of Romanian) attracted the nomadic Indo-European herders from the northern steppe, the warrior Kurgani, and that this put an end to the Turdaș and Cucuteni cultures.

But the rich valley of Danube attracted travelers from Western Europe too (Celtic tribes), marking the beginning of the Indo-Europeanization process (2700-1800 BC), as well as the evolution of the Thracian-Dacian civilization (10th century BC – 1st century AD).

The Neolithic culture of Petreşti, Transylvania

Petreşti culture was of Transylvanian origin, known for its rhombus, square and spiral patterns in red and brown. Needles and fishing hooks were made of copper, while gold was used for decorations made through hammering, marking the beginning of goldsmiths in Transylvania.

Decea Mureşului culture and Gorneşti with its (high-necked milk pots) , both present in Transylvania, are also worth mentioning.

Transylvania during the Bronze Age (3200 / 2700 – 1100)

Bronze Age Era left us a rich array of cultures, another proof of the busy life of prosperous inhabitants of Transylvania’s land as well as all over Dacia, and today’s land of Romania.

What was their everyday life like?

Farmers would use ploughs on the fields and this, as well as irrigation, would yield more crops in late summer days, the use of axes chopped down more trees, faster, and the use of domesticated horses made it easier for man to carry the wood where it was needed. Rafts went down the rivers. New homes, bigger homes, rose next to each other. Cities emerge. Walls were plastered, roofs were fixed, again and again, for man stayed put. Herders busied themselves with more cattle, more diverse too, which meant dairies were introduced in the diet, and more wool was available for more diverse clothes, warmer too. Then women would grind grain or tend hearths. Diverse metal working skills gave birth to household and luxury goods as well as fine jewellery. And women would gaze at themselves in obsidian mirrors. Trade in metals and goods took place over long distances. Some people grew rich and powerful. Society became more diverse.

The Coţofeni of Transylvania, Early Bronze Age

The mid-Danube and south-eastern central Europe, including Transylvania, experience now the Baden – Coţofeni culture. Copăceni culture develops in central Transylvania, in today’s Cluj county and along Someş rivers.

Their main pursuits were agriculture, animal breeding and ore extraction. Their pots’ rims are thickened and decorated with rope impressions, yet the most important development of this era is considered to be the single-edged axe.

Other cultures (Şoimuş and Jigodin) developed in parallel, in different areas of Transylvania.

The Golden Helmet of Cotofenesti, Geto-Dacian, 4th cent.BC @ National History Museum Bucharest

— Pat Furstenberg, Author✒🏰 #Im4Ro 🔛 bit.ly/Im4Ro (@PatFurstenberg) February 18, 2022

AND

(exciting to recognize) a replica worn by late💕Amza Pellea as Decebalus (King of Dacia 87-106AD) in The Dacians movie.#FindsFriday #Im4Ro #Dacia #Roman #Romania #history pic.twitter.com/NTl0k24N37

I would like to mention the Periam-Pecica on Mureş culture near today’s Arad city, while the Transylvanian Plateau saw by the Wietenberg culture, namely the Lăpuş group in today’s Maramures and Cehăluţ in Crisana. Most of these cultures have solar symbols (spirals, crosses with spirals, spiked wheels, rays) in their pottery design.

The sun still washes over the Mureş river. Below, a boatman tends to the ferry in 1900, it would have been a raft in the Bronze Age – once again the river becoming a bridge, as well as a source of food. Man, sun and water, a scene reminiscent of life thousands of years ago. Then, the Periam-Pecica culture, and the Lechinţa one, would have dominated the area, an innovative way of life like nothing the valley of the Mureş river has experienced before, gleaming bright for a few centuries, before fading.

It is from these times that the culture from Lechinţa de Mureş (Mureş county, Transylvania) left us a fragment of a cult wagon adorned with sheep-goat heads (protomes, adornments in the shape of an animal or human torso), as well as a a gold axe with a detailed engraving of a human and a bovine silhouette, part of the Ţufalău thesaurus (Covasna County, Transylvania).

Archeological findings dating from the Bronze Age and discovered in the intra-Carpathian space, Transylvania, tell stories of a settled population busy with farming (buckwheat, chick-peas and sesame seeds), animal breeding (pigs, oxen, sheep, goats, horses – the fast Dacian horses being renowned) next to apiculture, viticulture, hunting, fishing, crafting, tool making (metal scythes, sickles, spades, pickaxes, rakes) and metallurgy (iron, copper, silver, gold aplenty), and, of course, pottery. The establishments become further fortified during the 2nd millennium BC, presenting ditches and palisades.

Dacians living in today’s Transylvania and adjacent territories led a plentiful lifestyle, knowing a better, more diverse food that meant a longer life expectancy, over the 32.5 years average of the Neolithic era.

As this is Transylvania, we should remember the surrounding mountains that provided not only game and fruits, but also timber, copper, gold and silver, salt too, a treasured commodity. And the Greeks highly appreciated the wood from Transylvanian forests, ideal for boar building, and its salt.

Words of Dacian origin related to viticulture are still in use today in Romanian language: butuc (stump), strugure (grape), curpen (tendril).

The Transylvanian Horses of the Bronze Age

The presence of horses around the homesteads would have revolutionized the transport, the trade and the communications during the Bronze Age in Transylvania, as well as between Transylvania and the neighboring provinces.

Use of horses tells us of the use of wagons with big wheels, then with spikes, as well as of better roads. Men became more economically productive and thus they acquired a dominant position within the family and in society.

Why domesticating horses in Transylvania during Bronze Age was important

The domestication of horses during Bronze Age Transylvania is of great importance as it could have taken place even before the first known evidence of equine domestication, the Sintashta-Petrovka graves (approx. 2 800- 1 600 BC)

But above progress, the archeological findings prove that a well developed community was settled in Transylvania, the connection between humans and the ground being proof of a flourishing community,economically, socially and culturally.

The “Birth of the Metal” in Transylvania and its Symbolism

The ‘birth of the metal’ was the Bronze Age society’s view on metallurgy, namely on the conversion of minerals to metal by means of fire. It was a process accompanied by rituals, magic formulas, and chanting performed around the kiln.

Perhaps blacksmiths were the first wizards, for during the ‘birth of the metal’ they associated the ground with the woman’s belly, the mine with the womb, and the ore with the embryo.

The Transylvanian type axe was greatly exported, having been found in archeological sites near Bug river (Poland), Oder river (Czech Republic) or Elbe river (Germany).

Religion during the Bronze Age era in Transylvania

Plenty carvings of solar symbols were discovered, such as continuing spirals, simple crosses or crosses with spirals, spiked wheels, rays.

Cult practices would have been performed in group, marking human and yearly timelines, as well as in various outdoor locations (although remains of a great hall, a megaron, were found north-west of Transylvania, at Sălacea, Crișana county, Romania).

The 1 150 kg Treasure from Uioara de Sus, Alba, Transylvania

Bordering the Bronze Age and the Iron Age is the 1150 kg treasure unearthed at Uioara de Sus, Transylvania, containing arms, tools, jewellery, bronze cakes (5812 pieces) –source.

Only 1 000 steps away at Şpalnaca, also in Alba, Transylvania, two thesauri were unearthed, one weighing 1 200kg, of of thousands of items, and a second one consisting of 120 bronze items.

Finding gold during the Bronze Age in Transylvania

Transylvania’s mountains and valleys were abundant in copper, silver and gold. Through archeological findings we can be certain that the way gold was obtained (by mining on the surface or in the shallow valleys of rivers and landslides) and washed during the Bronze Age is not far from the ways of washing the gold-bearing stones today.

The archeological findings from Lăpuş, Maramureş, Transylvania, dating to Bronze Age are the richest assemblages discovered in the eastern contemporary Carpathians region (source).

Transylvania from the Iron Age to Roman Dacia(1 100 BC – 150 AD)

Exciting to this era are the number of similar findings spread over the entire Carpathian Danubian space proving that the culture of the Geto-Dacians developed and individualized itself from southern Thracians and other neighboring tribes.

From the historian and geographer Strabon (63 BC – 23 AD) we know that Dacians lived in the mountainous area of Transylvania, towards the valley of Mures river, while the Getae lived on the valleys neighboring Danube’s Big Boilers (Porțile de Fier) and all the way to where Danube met the Black Sea. Strabon also tells us that the Dacians and the Getae spoke the same language, while the Greeks considered the Getae a Thracian tribe.

The Getae were “the noblest as well as the most just of all the Thracian tribes”.

Historian Herodotus

Here is a little story about the humble nature of the Getae:

After Getae king Dromichaetes (300 BC) won the war against Thracian king Lysimachus (successor of Alexander the Great and ruling Thrace, Asia Minor and Macedon), to show his respect towards the bravery of the opponent army Dromichaetes ordered a great feast. During this feast the Getae ate with the same wooden spoons and plates they always used, while the Thracian prisoners and Lysimachus received gold spoons and plates and were afterwards released.

Thus, Dromichaetes wished to prove that a rich kingdom like the one ruled by Lysimachus is in no need of a poor land like the one his people occupied. Dromichaetes also release Lysimachus knowing that freeing an enemy king would bring them greater political advantage than his punishment.

“The Getae people are wiser than all barbarians and even wiser than the Romans.”

Dion Hrisostomos (40 – 120 AD), Greek philosopher

What is the Etymology of word Dac? From Warrior Nickname to Ethnic Identity

There are quite a few theories as to how the Dacian people received their name and the etymology of dac, dáoi.

In his book From Zalmoxix to Genghi Han, Romanian religious historian, philosopher and writer Mircea Eliade writes that when a nation’s ethnicity is the image of an animal, there is always a religious explanation behind it. A deity, or a mythical character that could change itself into a wolf or had special powers. But we don’t have such proof for our Dacians.

We know from Strabon that Dacians were the first to call themselves dáoi (wolves). In Phrygian, the language of the Indo-European people, dáos meant wolf. But it wasn’t only the Indo-European tribes that called themselves or were named after a wolf. In Spain, Ireland and England there were similar tribes too.

Another explanation is that dáos, dáoi, was the nickname given to:

Up until today one of the Christmas Romanian traditions asks of carolers to wear the mask of a wolf (goat or bear) during the twelve days before Christmas and until Boboteaza, Epiphany, January 6th.

So Dacians, this brotherhood of warriors, were the first to call themselves wolves, or those who are like the wolves, dáoi. And the name spread, especially during the ruling of Burebista and Decebalus, when Dacians emerged as brave warriors. Strabon writes that at any given time the Dacian army numbered 200 000 souls.

The name Dacians was especially used in writings by Latin historians, while the Greeks used the term Getae.

Celtic Tribes visit Transylvania IV – II BC

Celtic tribes from the West also visit the Danube plains and the north of Transylvania (they stopped short of Maramureş, in the north). Between 4th – 2nd century BC the Celts here established a co-existence and a fusion with the local population of Dacians that was still surpassing them in number.

Around 150 BC a rise in Dacian authority probably under the ruling of Dacian King Rubobostes sees the Celtic tribes thrown out of Transylvania heading southwards. Yet as long as the Celtic tribes shared common ground with Dacians, they coexisted in peace as artifacts prove – Celtic and Dacian graves fund side by side.

Over 600 archeological sites of which 26 fortifications from the First Iron Age, Hallstatt, were discovered across the territory of Transylvania, most of which were occupied at all times. The fortifications, davae (one = dava), had stone strongholds and were built on a system of circular belts allowing the defender, if such a stronghold was in danger of being lost, to retreated behind an inner belt through secret gates. The fortresses also had ditches, rampant and palisades.

Such fortresses were raised on inaccessible elevations, close to fresh water sources and fertile areas for agriculture. Within their walls there were metallurgical workshops that allowed Geto-Dacians to manufacture their weapons and tools, an indication that fortresses housed skilled craftsmen too, but weaving, spinning and leather manufacturers too.

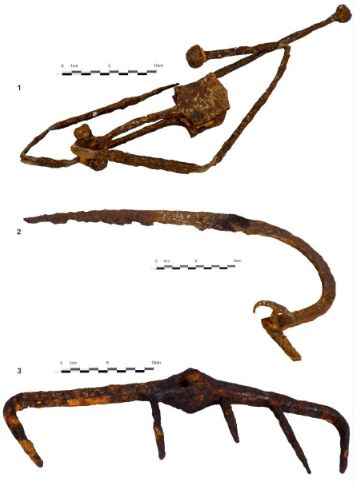

Above: wrought iron pliers, a mower, and an iron rake initially with six teeth – all Dacian Iron tools and weapons originating in the Orăștiei Mountains, dating 2BC-2AD, (from Brukenthal Museum, photo source).

Throughout the years fortresses were built as a defense against the Celts, the Sarmatians and the Romans.

Worth mentioning and all in Transylvania are the Dacian fortresses from Cluj, Dej, Huedin, Someşul Rece, and Orăştie Mountains (Hunedoara county) – Blidaru fortress. The fortified settlement from Ciceu-Corabia (Bistriţa-Năsăud County), or the 30 hectares Teleac fortress (Alba County) also bear witness to a well developed nation. During the 1st millennium BC the fortresses are further strengthened with stone walls.

Large quantities of animal bones were fund in or near such settlements, cattle, sheep, swine, a clear indication of domestic animals and the importance of meat in the daily diet.

Magic practice were linked with fertility rituals, the change of seasons too, while spiral and sun rays on pottery suggest a religion inclined to worship the Sun but also the underworld.

Dacian Gold Kingly Helmet of Coțofenești, Prahova County, Romania, approx. 400BC

Dacian Kingly Helmet of Coțofenești was made by hand hammering from one piece of gold.

Worth noticing are the eyes and angry eyebrows carved on it, supposedly with apotropaic powers, to avert evil influences or bad luck.

It indicates the existence of full-time craftsmen.

The helmet was unearthed in 1928 by a primary school child 🙂

When the Persians under Darius the Great marched through the Balkans, campaigning against the Scythians (found in central Eurasia), the Thracian tribes surrendered to Darius and only the Getae offered resistance.

According to Herodotus (ancient Greek historian), the Getae were “the noblest as well as the most just of all the Thracian tribes”.

Dacians and Dacia under King Burebista

During the middle of the first century BC the Dacians living on current day Romanian territory, especially Transylvania, were led by Burebista (82-44 BC) who even offered military assistance to Roman General Pompey in the civil war against Julius Caesar in 48 BC.

This time represents a classical period for the Geto-Dacian La Tène culture.

Burebista, “the first and greatest of the kings of Thrace.”

The Dionysopolitan decree made in honor of Acornion

and,

“leading his people, the Dacians, Burebista raised them so high that even Romans feared him”

Historian and geographer Strabo (63 BC – 23 AD)

While Dacian kingdom reached its widest borders under his ruling. And it was Burebista who moved the location of the capital city from Argedava (perhaps today Popești, Mihăilești district in Giurgiu County, Muntenia)to the newly built Sarmizegetusa and tightened the religious reigns on his people with the help of Dacian’s Great Priest Deceneu (philosopher, astronomer, who also ruled Dacia after the political plot that eventually killed Burebista in 44 BC).

Deceneu, the great King of Dacians from Transylvania

From 6th century Roman historian Jordanes and his work Getica we know that Deceneu became a great king that not only ruled over all the Dacians of Transylvania, but also taught them philosophy, physics, astronomy, how to follow and use the phases of the moon in agriculture, the zodiac signs and the art of war, but most of all theology and how to be good Christians and stray away from the cult of wine and Dyonisos’ sacred grapes – something Dacians were quite fond of.

As with most fortifications of political and military importance, they often turned into large villages.

The Geto-Dacians worships one god, Zalmoxis, their religion being centered on three beliefs:

Dacians also had wide medical knowledge (as proves the medical chest discovered at Sarmizegetusa), were skilled in astronomy (at Sarmizegetusa there is still visible a calendar-temple), and according to Romanian historian Constantin Daicoviciu Dacian scholars used first the Greek alphabet and then the Latin one, under the Roman occupation.

Dacians under Burebista and the Silent Temple of Sarmizegetusa

As the Roman Empire expanded, its fleets advanced along the Rhine and the Danube to protect its borders.

I do remember learning about the first Roman – Dacian confrontation and how the Romans crossed the Danube on a bridge made of boats in a spot close to today’s Iron Gates (Porțile de Fier).

Decebal defeated them at Tapae, a natural passage through the mountains, in an attempt to guard Sarmizegetusa, Dacia’s main political city.

It was here, in Orăștie Mountains, that Dacians built a series of over 40 highly reinforced fortresses.

Sadly, after Burebista the great Dacian kingdom fragmented itself and different kings ruled the smaller kingdoms that emerged until Decebal (87 -106 AD) came to power, “skilled in the art of was and a great leader and tactician,” and united almost all the Dacians that Burebista had ruled over.

Sarmizegetusa Regia was built over five terraces on an area covering around 30,000 square meters. The walls were raised using the murus dacicus technique invented by Dacians, Latin for Dacian walls, using regular-sized stone blocks and no mortar.

The sacred area of ultimate importance comprised of a large circular and a rectangular sanctuaries and several smaller temples whose columns are still visible today. Seven sanctuaries had been unearthed, dedicated to Mars, Saturn, Jupiter and Triads, Mercury, Venus, the Moon, while the 7th is the Dacian Pantheon.

An artifact still present at Sarmizegetusa Regia is the Andesite Sun, a massive circular block of rock, 7 meters in diameter, used as sundial. Ten rays are encrusted upon its surface. The Andesite Sun’s solar rays point to the peaks of surrounded mountains. A pavement of Andesite slabs arranged like rays around it for the Sacred Precincts.

The Legacy of the Dacian Civilization

The legacy of the Dacian civilization is overwhelming, not in the least limited to artifacts and a vast number of known and unknown archeological sites. And not limited to the territory of modern day Romania either, for from a Geo-political point of view Dacia (as the Romanian provinces have been throughout the centuries) was a true frontier, a buffer zone, zone between empires and cultures, between East and West; the Byzantine Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Russian Federation in the East and the Western European powers, Hungary, Austria, Poland, Germany.

Roads from Greece, Rome and Egypt passed through Dacia. Riches from its underground spread around the world From language to music, from traditions to legends, the Dacian legacy played a decisive role in the shaping of the fecund Romanian folklore, part of which created the scaffolding on which Transylvania and with it the greatest Romania reveal themselves and continuously markets themselves to the world.

Europe during 1 BC must have been an interesting time, with so many tribes mingling and influencing one another, much like the waves of an ocean spilling on sandy shores.

Yet three nations were standing out, the Romans, the Celts and Dacians.

Still to follow:

Transylvania during the Roman Dacia until 4th century AD

Wish I May, Wish I Might, Own Transylvania by Tonight

Stories and History of Transylvania, the Middle Ages

Romanian Transylvania, It’s Origin and Etymology

Sources for Stories and History of Transylvania, Prehistory to Roman Dacia:

Astalos C, Sommer U., Virag C., Excavations of an Early Neolithic Site at Tăşnad, Romania

Boroffka, N., Depozitul de la Uioara de Sus/The Deposit from Uioara de Sus

Comsa, A, Szücs-Csillik, I., Andesite Sun in Carpathian Mountain

Dacus M., Proiectul ‘Romania Enigmatica’

Eliade, M., De la Zamolxis la Genghis-Han. Studii comparative despre religiile şi folclorul Daciei şi Europei Orientale, 1980

Floru, Ion S., Istoria Romanilor, Cursul Suoerior de Liceu, 1929

Kacsó, Metzner-Nebelsick, Nebelsick, New Work at the Late Bronze Age Tumulus Cemetery of Lăpuş in Romania

Larousse Encyclopedia of Ancient & Medieval History

Love novels filled with history?

So much fascinating history to learn about. I was agog when I saw the image of the 33,000-year-old skull. That’s mind boggling, and the injury is so clear even after all this time.

Yes, I thought so too. And I am sure there is a fascinating story behind it 🙂

I learned a lot while researching this, go myself knee-deep as you see. Discovered I know a lot less than I thought I did!

Thank you for visiting, Priscilla 🙂

Excellent! 🙂

Thank you so much, Paul!

Iti multumesc din suflet 🙂

Patricia, faci mai multe pentru turismul românesc decât Guvernul României. 🙂 Am o observație, însă. Nu Burebista, ci Decebal i-a invins pe romani la Tapae.

Ah, ai dreptate, Jo. Multumesc mult de tot. Mea culpa.

Dar n-ar fi exclus ca stafia lui Burebista sa fi bantuit campul de lupta 🙂

Perhaps if you miss it enough and you find it fascinating, you feel compelled to write about it?

Write about what? My country? Encourage tourism? 🙂 Eh! Not my cup of tea!

I very much appreciate your fascinating presentation about Dacians and their amazing legacy or the leader Decebal, the great leader and tactician. Many thanks:)

I believe we have the archeologists to thank for this, for telling us such vivid stories while only having bits of pottery, pebbles along a road, and some columns left to look at 🙂