When Emperor Trajan marched north to face the Dacians, it wasn’t just another Roman campaign. It was personal. The Dacians, led by their fierce king Decebalus, had grown too rich, too proud, and way too independent. For Rome, as a winning empire, Dacia was both an embarrassment and an obsession.

Emperor Trajan, famed for his fairness and restraint, crossed the Danube not merely to conquer but to complete a destiny. His soldiers built altars for their dead while at the same time raised a bridge over the roaring river, an architectural wonder meant to defy time itself. And then the Romans entered Dacia. Yet King Decebalus had one last act to play. Knowing defeat was inevitable, he diverted a small river near his fortress at Sarmizegetusa and buried his treasure, the Dacian’s gold, beneath its bed: gold, silver, jewels, the wealth of a dying kingdom. The river was returned to its course, the captives who had helped him silenced forever.

We know this because Roman historian Cassius Dio wrote that the Dacian king “diverted the course of the river Sargetia, made an excavation in its bed, and into the cavity had thrown a large amount of silver and gold and other objects of great value,” then restored the river and “made away with the captives to prevent them from disclosing anything.”

How come a Roman historian knows this? It was Bicilis, one of Decebalus’s companions, who later betrayed the secret to Trajan.

Some chroniclers claimed the hoard weighed more than one hundred and sixty tons of gold and three hundred of silver, an unimaginable wealth mined from the Apuseni Mountains, the 1500-kilometer spine of stone rich in ore and legend that bordered Dacia in the west. In those mountains, people were said to have buried their gold with their dead, or hidden their treasures from marauders. Even today, fragments of Dacian bracelets surface in the soil like echoes of a vanished empire. (Bolundut, Ioan-Lucian. (2025). Gold Mining in Dacia After the Roman Conquest. Mining Revue. 31. 50-61. 10.2478/minrv-2025-0004).

Rome found the hoard, at least most of it. Ancient sources claim Trajan returned with enough spoils to build his grand forum and the column that still winds upward in marble, telling the story of conquest and loss. For example, in his Epitome of Books Cassius Dio tells of the staggering riches – gold, bronze, marble – hauled to Rome after the Dacian Wars, enough to fund a new forum and 123 days of revelry. He adds that King Decebalus tried to hide his treasure in mountain caves, only for the Romans to uncover and claim it in the end.

Yet legends lingered in the Carpathians: that part of Decebalus’s treasure escaped Roman greed, sleeping beneath the waters of the Strei River, guarded by the unseen spirits of the mountains…

But were they marked on any maps? None that survived, as far as we know.

If you’re wondering, the contrast between Roman and Greek thinking shows itself in the way the Romans drew their maps (some engraved in temples). While the Greeks chased precision – circles of latitude, lines of longitude, star measurements, clever projections – the Romans wanted something useful: a map that could move legions, guide governors, and keep the vast machinery of their empire running. Practical rods over perfect theory, the Roman way. And we know that Romans used maps from many re-written works of Roman authors that mention this.

Do note on the map above how the continents are depicted with Asia (east) at the top of the map, hence the term “orientation”. Being a Roman map, one made for practical, administrative, and military purposes, its emphasis is upon Rome as reflected by the out of proportion shape of Italy, making it possible to show Italian provinces. Also, most of the map is devoted to the Roman Empire. Dacia is also present, to the left of the map.

The 2nd Century Ptolemy World Map

Claudius Ptolemy’s Narration of Geography in the 2nd century AD laid the foundation for mapping Dacia, introducing cartographic projections that allowed regions and locations to be represented mathematically. Drawing on Roman military maps, Trajan’s accounts of the Dacian Wars and earlier works by Marinos of Tyros and Vispanius Agrippa, Ptolemy recorded the positions of 15 Geto-Dacian tribes, 42 settlements ending in “-dava,” and several Roman towns.

His map shows Dacia’s borders as the Carpathians to the north, the Tisa River to the west, the Danube to the south, and the Siret River and Black Sea to the east, roughly corresponding to the kingdom of Decebalus before Rome’s conquest. Ptolemy’s work preserved a detailed picture of Dacia’s geography and tribes, blending contemporary knowledge with older sources, and remained a key reference for Renaissance cartographers.

The present form of the Ptolemy map was reconstructed from his coordinates by Byzantine monks under the direction of Maximus Planudes after 1295.

12 Gold Ducats for a Map (12 x 3.5 grams gold)

In 1502, as Europeans hungrily turned their gaze toward the vast, uncharted lands across the Atlantic, maps became more than instruments of navigation, they became instruments of power. A single inked coastline could change the fate of nations.

The Italian spy Alberto Cantino understood this all too well. Working in Portugal on behalf of Ercole I d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, he acquired a map so valuable, so dangerous, that it could alter borders and ambitions alike.

Knowledge was currency and no treasure was guarded more fiercely than the secret geography of the world. The “Cantino Planisphere,” the earliest nautical map that still exists, completed in Lisbon that same year, recorded discoveries still hidden from public eyes: new continents, unseen rivers, trade routes stretching toward the edge of empire. Comprising six sheets of parchment sewn to canvas, this remarkable chart—four feet high and eight feet wide—depicted both the known and the forbidden.

To steal such a map was to steal a kingdom’s future. And yet, Cantino did.

Whether he bribed a royal cartographer or slipped through the guarded halls of Portugal’s nautical archives, history does not say. We only know that he paid twelve gold ducats for his prize – a fortune for a map, but a trifle for a spy who understood the worth of secrets.

Maps have always tempted thieves, kings, and dreamers alike. They hold what gold cannot buy: the promise of discovery. And centuries after Cantino risked his life for a chart of the New World, other maps, older, inked in darker ages, would stir the same hunger.

Other ancient maps are only rumored, although the rich province of Dacia was included on many Roman maps after its conquest. Some maps of ancient lands were even created hundreds of years later, such as the Vetus Descriptio Daciarum nec non Moesiarum, an antique map of ancient Dacia and Moesia corresponding to moder-day Romania nd Bulgaria. But this map was engraved by Petrus Kaerius (Pieter van den Keere, a Flemish engraver, publisher and globe maker) around 1650s, based on classical sources such as the work of Ortelius and the descriptions from Ptolemy’s Narration of Geography.

The Legendary Dacian Treasure Map

Legends tell of one such map, a parchment said to reveal the buried hoards of ancient Dacia, its fortresses tucked among the Carpathians, its gold veined beneath Transylvania’s roots. Like Cantino’s stolen planisphere, this map too was whispered about in courts and taverns, a fragment of power that could make or unmake an empire. While the Dacian gold left behind by the Romans appeared here and there throughout the centuries, discovered by chance (or not) by the lucky few.

I found myself wondering whether it was mere chance that so many, across so many ages, managed to unearth yet more Dacian gold.

For what is a treasure map, after all, if not the purest symbol of mankind’s oldest desire: to possess what should remain lost?

I played with this idea. Therefore, centuries later, these legends surface again, in When Secrets Bloom.

“‘Vlady, look at this!’ Fro Rivka’s voice trembled with excitement. ‘This mark—it matches the old tales of King Decebal… Believed to be concealed under a riverbed by the king himself…’”

The novel picks up where history leaves off. A stolen map, a dragon-marked parchment, whispers of the Dacian Draco flag, the standard that once shrieked like wind in metal terrorizing Rome’s legions. Vlad, heir to the fractured legacy of Drăculești, and Fro Rivka, the woman-scholar who dares to read what others fear to see, find themselves standing on the fault line between legend and truth.

“The legend has it—my father told me—that the swift waters of a river called Strei by Dacians and Sargeția by Romans could reveal treasure to the pure at heart… Buried beneath its bed, nestled in the roots of an ancient tree, Decebal’s hoard: gold coins, jewels, the last wealth of a dying king.”

Where history ends in marble relief, When Secrets Bloom begins in flesh, fire, and blood. It reimagines the power that gold once held – that gold that built empires, that crowned tyrants and broke them. And, like the Dacian treasure itself, the truth in this story lies buried beneath layers of time, waiting for those bold enough to uncover it.

Another Stolen Map: Secrets of the Tabula Peutingeriana

Every empire leaves behind a trail – of stone, of blood, of ink.

If Decebalus’s treasure was buried beneath a river, then Rome’s other treasure was hidden in plain sight: a map. Not of gold, but of knowledge. A map that promised the world.

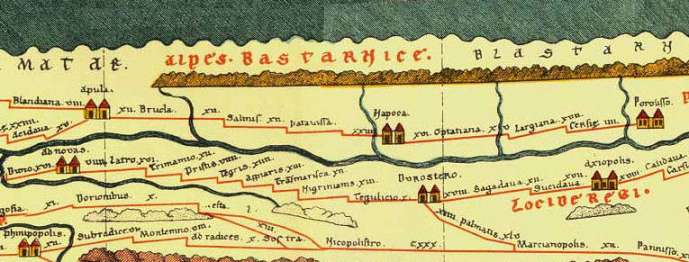

The Tabula Peutingeriana, or Peutinger Map, is the only surviving map of the Roman cursus publicus: the state-run network of imperial roads that laced the ancient world together.

Imagine a scroll nearly seven meters long, stretched like the skin of a serpent, tracing routes from the misty shores of Britain to the edge of India and even a faint mark for distant China. Why so disproportional? It was never meant to show geography as we know it. It was a traveler’s dream, a roadmap of empire, listing 555 cities and more than 3000 place names. The world not as it was, but as Rome claimed it.

The map we know today was copied in the Middle Ages, around 1265, likely by a monk in Colmar. Eleven pieces of parchment sewn into one, it survived not because it was beautiful, but because it was useful: the veins of empire rendered in ink.

But like all things of power, it too became the object of theft.

In 1494, a German scholar named Conrad Celtes discovered the map in a library in Worms. He was a man obsessed with Rome’s legacy, determined to connect the German Roman Empire to the glories of the Caesars. Celtes never published his find. Instead, he quietly passed it to his friend, Konrad Peutinger, a humanist and antiquarian in Augsburg. After that, the map’s trail grows murky.

Scholars later accused Celtes of theft, of stealing not merely a parchment but a link to history itself. For the map’s origins were erased, its first three centuries lost to silence. Johann Eck, a theologian of the time, called the act a desecration. Even today some historians argue that to call it the “Peutinger Map” is to honor the pilfering.

For centuries, the map passed between noble hands: princes, dukes, emperors — all eager to own the world reduced to a single scroll. It rests now in Vienna, too fragile to display, too haunted to forget.

And yet… questions remain. How did Celtes truly come by it? What clues did he and Peutinger erase? And why do several versions of the map appear to differ — especially around the territory once known as Dacia?

In When Secrets Bloom, that’s where the story begins again.

A scholar in Transylvania discovers a torn vellum sheet, its ink faded but its markings unmistakable — a fragment of the Peutinger Map, showing roads and fortresses that no longer exist. And beside the Roman routes, a faint carving of a river twisting through the mountains — marked not with Latin, but with a sigil: a dragon.

“This isn’t a copy,” whispers Rivka, her hand trembling. “It’s older. It’s the original route to Sarmizegetusa… before they changed it.”

In that moment, history folds in on itself. The lost treasure of Decebalus, the stolen Peutinger Map, the ghosts of Rome and Dacia — all converge into one truth:

Some maps don’t lead you to where you’re going. They lead you back to what was buried.

Maps, especially of roads, were once more than mere parchment, they were living memory. The elusive Peutinger Map, for instance, was just one of many ancient cartographic documents that have since vanished, lost to neglect and to the absence of scribes to copy them.

What survives now are fragments of itineraries, hints of routes, and the enduring portolani (navigation manuals) of the seas. While land roads, it seems, last longer in spoken memory than in ink, passed along by travelers and traders long after the original charts crumbled. In the hunt for Decebalus’ treasure such maps were more than guides; they were keys to history itself, capable of unlocking the hidden veins of a lost empire.

In the end, the true treasures are not merely the gold carried off by emperors or the hoards swallowed by rivers but the maps, those fragile shards of memory that survived conquest, betrayal, and time. They remind us that every empire leaves shadows, every king buries secrets, and every river carries whispers of what it once hid. And if a single torn vellum can rewrite the fate of a kingdom, imagine what might surface when legend stirs again. Some treasures wait not to be found, but to be remembered.

That was very interesting history and maps. I have to admit it is hard to believe that one hundred and sixty tons of gold and three hundred tons of silver was hidden away. That is 15 billion dollars worth of gold and silver in today’s value and gold and silver was even more rare back then.

Hard to imagine, indeed. I should have included the research paper, sorry bout that. But I did now: Bolundut, Ioan-Lucian. (2025). Gold Mining in Dacia After the Roman Conquest. Mining Revue. 31. 50-61. 10.2478/minrv-2025-0004. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/390396579_Gold_Mining_in_Dacia_After_the_Roman_Conquest