The Roman Army went through great pains and two bloody wars to conquer the great nation north of Danube, be rid of its threat over the Roman lands nearby, and own the riches of its land, so life changed in Transylvania too, during the times of Roman Dacia, until 4th century AD.

Learn about Transylvania during the Roman Dacia and until 4th century AD below or time-travel and jump to a chapter:

How and Why Dacia Became a Roman Province?

Transylvania during Roman Dacia

Everyday life of Dacian people of Transylvania during Roman Dacia

The folklore and culture of Dacia and of the old Transylvania

The Religion of Dacian people

What happened in Transylvania during Dacia’s Romanisation?

Why Romanisation caught in Dacia

The years of Roman Withdrawal from Dacia

Who remained in Dacia (and in the intra-Carpathian land of today’s Transylvania) after Roman withdrawal?

Christianity in Dacia (including Transylvania)

Romanian liturgical language rooted in the Latin language

Archaeological proofs of Romanian Christianity and continuity in Transylvania after 2nd century AD

How and Why Dacia Became a Roman Province?

During the first century AD Decebalus (the future King of Dacia 87-106AD, today Romania) raided the provinces of Moesia. The Moesian governor reached some sort of an agreement with Dacian King Decebalus. By paying the Dacians a yearly payments of gold, the Dacian King promised to withdrew from Moesia and not invade it again (and not to sack cities and take prisoners).

But paying a tribute to a small province such as Dacia did not agree with the big boys of Rome. The Senate of Rome and the army saw it as a sign of weakness on their part.

The Domitian Wars Between Rome and Dacia

As a result during the next year, 86 AD, Roman legions crossed the River Danube into Dacia. They were met by Decebalus who led the army of valiant Dacians and defeated the Romans. The Roman ruler was killed in battle, the Roman flag was captured. Some historians say that during this battle the Roman Legion V Alaudae was annihilated, as the legion disappeared from the Roman legion’s list.

Roman Emperor Domitian returned to Rome to think…

As a result, two years later in 87-88AD Roman commander Tettius Julianus arrived in Dacia with more Roman legions and Romans fought the Dacians at the First Battle of Tapae. With Sarmatian crossing the frozen rivers into Moesia, part of the Roman legions retreated to protect this Roman territory.

It was after this victory that the Dacian leader Duras-Diurpaneus received his new name known of Decebalus translating to “as strong as ten wild men”.

After subsequent battles Roman Emperor Domitian accepts a peace offering from Decebalus: a yearly payment of gold to the Dacians.

The Dacian Roman Wars under Emperor Trajan

Emperor Trajan was kin to demonstrate his military leadership. Trajan spent almost half of his reign away from Rome, in military campaigns.

He first came to Dacia with ten legions of Roman soldiers, nearly 100 000 men, then be brought in more. Romans would start their attack marches in May, when the earth was dry and there was enough grass underfoot to feed the horses, for they covered 30 kilometers a day, 20 Roman miles, only to fight in June – July. Ahead, squads searched for food, spies, clues, trees were cut, roads were build. Behind, a Roman legionary carried a load up to 45 kilograms, as much as a contemporary soldier or Marine fighting in Afghanistan.

Roman Army did overpower the Dacians by its number, weapons and strategies, but Dacians under King Decebalus fought until the last man – and these are stories told on Trajan’s Column in Rome which, by the way, was financed with the spoils of the Roman-Dacian wars, as were a new Roman forum, the Baths of Trajan, Trajan’s Aqueduct, and Trajan himself.

The Tale of Roman-Dacian Wars Carved on Trajan’s Column

Emperor Trajan did wrote his own accounts of Dacian Wars, Dacica, one sentence survived:

“inde Berzobim, deinde Aizi processimus“

EmperorTrajan wrote in Dacica describing the opening attack on Dacia

meaning

“We then advanced to Berzobim, next to Aizi.”

Today we have the Trajan’s Column, a spiral bas-relief of 155 scenes as a primary source for the Roman-Dacian wars.

A warrior as versed and ambitious as Trajan would have first studies his opponent, King Decebalus, a skilledfighter who excelled in ambushes and pitched battles but a great leader too, be it in victory or defeat. When Trajan and his many legions left Rome and advanced towards Dacia, in the Spring of 101AD, the moment was well chosen. When the Romans reached Danube River King Decebalus initiated peace talks at first (perhaps his tactic to slow down the Romans). After the talks failed, Decebalus’ warriors quickly attacked the most advance troops of the Roman army. It was Trajan’s turn to initiate peace talks, but Decebalus refused. Consequently, Trajan’s army took the mountain pass attacking the Dacian fortresses.

The Second Battle of Tapae took place now. Then, with the onet of winter, two more fierce battles, the Battle of the Carts and the Battle of Adamclisi. A heavy winter frozen in waiting followed.

Trajan and the Roman troops returned in 102AD. During these battles Decebalus’ sister was captured followed by Decebalus accepting heavy peace talks: the previous tribute paid via the old Domitian treaty wasnulled AND Decebalus had to surrender an area in western Dacia for future Roman settlers.

But peace was not in the Gods’ plans.

It was the summer of 104AD when Decebalus lerned that Trajan was growing his forces along the Danube. When a Roman legate was sent into Dacia for further peace talks, Decebalus had him arrested. Decebalus planned to use the Roman legate as leverage, hoping to exchange him for the land he’d lost to the Romans the previous year. Again, negotiations failed and Decebalus attacked the nearest Roman forts. Trajan responded to war, but this time he arrived by water, via Adriatic and up the Danube, to Drobeta – to Trajan’s Bridge built previously by Apollodorus of Damasc. By summer, Trajan’s legions knocked into Sarmizegetusa‘s gates, the Dacian capital.

While Trajan’s army was knocking on the fortress’ walls, Decebalus had his people set the huts alight and it is said that many even poisoned themselves, as to not fall into the Roman hands and become slaves in Rome. While he, Decebalus and his most trusted me ran into the mountains, in the deep forests, where they buried the extremely large Dacian treasure… This is an entire tale all on its own…

Before he could be taken prisoner King Decebalus killed himself as well – Over 50 000 Dacians were taken prisoners and brought to Rome, together with part of the Dacian thesaurus. Emperor Trajan earned the title of Dacius while the celebration in Rome lasted for 123 days, 10 000 gladiators fought and 10 000 animals were slaughtered.

I wrote many tales about the Roman Dacian wars in my latest books, Transylvania’s History A to Z and Dreamland:

The Romanian land we know as Transylvania, during Roman Dacia

Thus, Dacia became a Roman province after the two bloody Dacian – Roman wars ((101–102, 105–106), and will remain like this for two more centuries. Romans burned Sarmizegetusa Regia from Grădiştea Hill, the ancient capital of king Decebalus (the last king of Dacia, 87 – 106 AD) built of bricks and wood, to the ground.

So little is known about the Dacian language. Although the elite of the Dacians, its priests, nobles, the administration, was literate, any records must have been destroyed in the aftermath of the Roman conquest.

After finally conquering the Dacians, Emperor Trajan was so chafed with himself that he ordered a marble column to be built in Rome, adorned with bas-reliefs that will tell the story of his conquest of Dacia, as well as the bravery of Dacians. Trajan would have been mighty proud of this conquest as Dacia, with Transylvania at its heart, was a rich land. It is with the the Dacian gold that Trajan embellishes Rome with a Forum and Baths in his name.

Below is a scene from Trajan’s Column depicting the Burning of a Dacian Town:

* We can see in the front, left, two Roman soldiers torching Dacian wood houses held together by nails, built on planks, with wooden fences.

* There are even a few Roman skulls stuck on poles along the brick wall of a Dacian fortress – yet Romans have decapitated many Dacian warriors too, as depicted in other scenes of Trajan Column.

* Front center, we see Dacian soldiers retreating towards the woods; they carry oval – round shields curly, have long hair and beards. They don’t wear hats as only high rank Dacians were a allowed to cover their heads with tarabostes. They wear long pants.

* In the center foreground we can see the Dacian Draco flag, a wolf’s head on a serpent body. When wind blew it produced a howl, wolfish sound, thus intimidating the adversary.

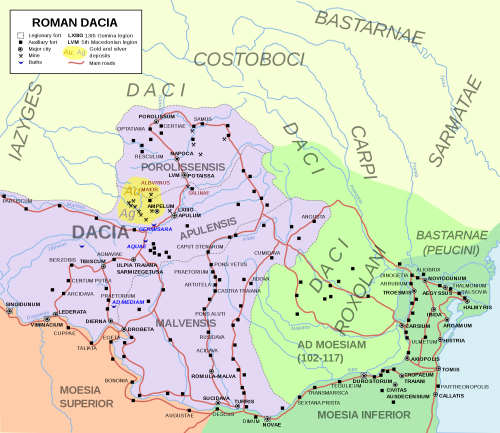

29 June 120, First Documented Mention of Province Dacia Superior (today Transylvania, Banat and west Oltenia)

When Roman emperor Hadrian (117–138) reorganized province Dacia (named Dacia Augusti by Romans) – because of repeated attacks by the Sarmatians (tribes from further East) – the provinces of Dacia Superior, Dacia Inferior and Dacia Porolissensis appeared.

Military diplomas from Porolissum (today the village of Moigrad, Sălaj county) and Cășei (Cluj county) mentions Dacia Superior and its governor, residing at Apulum (today Alba Iulia) with the XIII Legion Gemina.

Everyday life of Dacian people of Transylvania during Roman Dacia

During these times, the Dacians of Transylvania mined the ground extracting iron, gold, copper, and salt; grew grains, vineyards, had herds of cattle. They were skilled craftsmen, turning metal into nails to build homes, tools to farm the land, weapons to protect their own – such as the falx, a two-handed sword curved at the tip and later adopted by Romans as a siege hook.

Transylvania’s Dacians would trade too, traveling southwards and eastwards on their horses, for the borders of Dacia extended all the way to the Black Sea.

The folklore and culture of Dacia and of the old Transylvania

Rituals connected with important life stages, as well as with religion and war, often involved music and dance. We know that Dacians made music using the whistle, the drums and, as Ovidius said, ‘whistles held together by resin‘ (panpipes), as well as magadis, a Dacian harp. War dances were also performed, especially involving a group of men dancing together holding weapons, the flax or a dagger, and also the mace, the mace remaining one of the favorite weapons of the Romanian peasant.

The Romanian bucium, the Carpathian horn use especially by shepherds, has its origin in Latin buccinum, bent horn. Its sound was meant to send signals, announce life-changing events, but also announce the Judgement Day (when played by Angels).

Listen to these peaceful Carpathian horn signals from Transylvania:

The Religion of Dacian people, Symbols and Symbology

The Dacians were spiritual people. They worshiped the sun and believed that afterlife existed, and was far better than the brief earthly existence. As many populations of their time, they lived in harmony with nature’s rhythms. They had a special bond with their God as is depicted in the cosmological symbols and patterns they used in their everyday life, and art.

Dacian war dance, the origin of Transylvania’s Călușari?

Could it be possible that the Dacian war group-dance represents the origin of the Călușari dance traditions, still very much present all over today’s Romanian territory?

Today, the Călușari use a staff and are still known for “their ability to create the impression of flying in the air” as Mircea Eliade said, a dance move he believed represented the galloping of a horse (remember the fast horses Dacians were renowned for breeding?) as well as the dancing of the fairies, namely Diana, the patroness of countryside of hunters, and of Moon.

It is this lyrical quality of Dacian folklore that proves, in the view of B.P.Hașdeu, Romnian writer and philologist, the continuity of Romanian people on these lands, since Dacian times.

What happened in Transylvania during Dacia’s Romanisation?

Most of today’s Transylvania was included in Roman Dacia either in 102 or later, in 106 (except for its north, Maramures, and north-west, Crisana). Other provinces of today’s Romania that were included in Roman Dacia were Banat, Oltenia, and west of Muntenia. Dobrogea (south-west of Romania today) was part of Roman province Moesia Inferior, as were most of west Muntenia and south of Moldavia.

But there were free Dacian lands too, the ones not incorporated in Roman Dacia at all. It makes sense to imagine that when Roman soldiers set foot in Dacia and especially after the two bloody Dacian-Roman wars, part of the local Dacians fled to join the free Dacians. But some remained. And it seems that part of the Dacians who fled returned, some years later.

Two major the Roman legions stationed in Transylvania during Roman occupations, 13th Gemina Legion, LXIIIG, at Apulum (today Alba Iulia) and 5th Macedonica, LVM, stationed at Potaissa (today Turda, Cluj County, where my mother was born). Besides these two legions, other auxiliary Roman troops settled in Dacia Romana, bringing along a mix of Roman soldiers originating from all the corners of the Roman Empire – sharing one common language, Vulgar Latin, the common speech.

Were the Roman soldiers happy to leave their families behind, all for the sake of conquering strange lands, for fame and kill? Some think they were, for they had a great leader, Emperor Trajan.

“He was a great general, mastering all the secrets of military art and bearing all hardships and sufferings of the war together with his soldiers who worshiped him for it. Besides military virtues he also had those of a civilian ruler.”

Constantin C. Giurescu on Roman Emperor Trajan, The Making of the Romanian People and Language.

With such faithful warriors Trajan colonized Dacia, most of his men speaking vulgar Latin, the common speech. The colonizers, at least some of them, eager to go on with their lives on strange lands would have married Dacian women adopting, even partially, the local lifestyle, learning the Dacian language and, in turn, teaching Latin to their families. Learning local traditions and culture and, in turn, sharing their own.

All in just over 150 years, while the Roman occupation lasted in Dacia, 107 – 271/276. But those were different times, with an average life expectancy of 30 to 35 years, slightly longer for women. So what looks like two generations today, meant four or five generations during Classical Rome.

How else?

True, adopting the Roman culture did not caught in Pannonia (present-day parts of Hungary, Austria, Slovenia, Croatia, and Serbia), nor in Britania (today Great Britain), each with nearly 400 years of Roman ruling.

Why Romanisation caught in Dacia (and in Transylvania)?

Then why Romanisation caught in Dacia? Surely not only because Roman soldiers married Dacien women and started families. But also because many other Roman soldiers were of Dacian origin. The service in the Roman army lasted for 25 years, after which the soldiers received Roman citizenship extended to every member of his family – no matter where they’ve been born. So a Roman sldier, apart from being fluent in Latin, he would have dopted, at least up to a point, the Roman culture. And if he had distinguished himself in fight, he would have been rewarded with land too, land from a Roman colony, such as (Transylvania and) Dacia.

Truth be told, Romans did a lot of hard work in the lands they conquered. Such as bringing their own administration for Dacia was an imperial province now, building roads, establishments for their troops that later turned into urban centers with rural area nearby, and bringing missionaries too. And the roads would have brought merchants and travelers and a flourishing economy. Roman missionaries would have brought a public worship service sung in Latin and a sense of community that would have planted the seed of peace and hope in the harts of the Dacians.

King Decebalus escaped the Roman pursuit only to commit suicide than be taken prisoner. Many Dacians were sent as slaves to various Roman colonies bordering Danube, and the Roman settlers made a new life in Dacia, building the new Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa some 40 km away from the Dacian Sarmizegetusa and near Haţeg.

But the Dacians who remained hidden in the forests and mountains would often revolt, thus Romans were soon forced to bring colonizers from Pannonia, Thrace, Moesia, Macedonia, Gaul, Syria and other provinces, in an attempt to overpower these Dacians. The Latin language was imposed locally for admin purposes.

The years of Roman withdrawal from Dacia (including Transylvania)

Yet no Empire ever lasted forever and under the Roman Emperor Gallienus (253-268) and again under Aurelian (270 – 276 AD) the Romans withdrew from Dacia Trajana considered now too difficult to protect under the threat of Carp and Visigoth tribes.

Between these two Roman withdrawals, Roman Emperor Claudius ‘Gothicus‘ (268-270) did reclaimed Dacia, defeating and destroying the force of Gothic cavalry during the battle of Naissus (Niş, Serbia today) – which earned him his nickname, Gothicus. The Goths fled, but not to Dacia, since they did not lived there, but to Thrace and from there on their ships further north, to south of Russia.

Already in 117 AD, after the death of Emperor Trajan and under Emperor Hadrian, Dacia was nearly abandoned as Asian tribes were eating up at the far western border of the Roman Empire so Hadrian had chosen to abandon the Roman Asia provinces annexed by Trajan. Hadrian was also thinking to abandon Dacia at that time, but his advisors changed his mind at the last minute pointing out that too many Roman citizen will be left at the hands of the barbarians, and that Dacia had an advanced administration and a great number of Roman colonists, unlike the far west territories. Plus it had riches too.

Eventually, the neighboring tribes that kept attacking the Roman province Dacia year after year became the final drop that coincided with the weakening of the Roman Empire after 234 AD.

After the second Roman withdrawal from Dacia, under Aurelian, the Roman Emperor created Dacia Aureliana, a small territory south of Danube, between the two Moesiae, perhaps as a reminder of great Dacia Traiana. Here it is said that he brought from old Dacia Traiana the remainder of the Roman soldiers and the Roman citizens.

Who remained in Dacia (and in the intra-Carpathian land of today’s Transylvania) after Roman withdrawal?

When Romans left the Dacian territories they occupied for approximately 165 years, two categories of Dacians were left behind. The people from the occupied land, the Roman Dacia, and the free Dacians still living outside the Roman Dacia.

Many Roman soldiers were of Dacian origin, so when they were forced to leave Dacia with the Roman army, and their families would have joined them. Romans involved in administration, civil and military, left too. Perhaps some craftsmen and tradesmen whose earning relied heavily on the army would have also left, but not all .

What the Roman retreat from Dacia did not intent was to give up the wealth of Dacian resources.

Romans still wanted access to Dacian minerals, gold, silver, iron, grains, honey, livestock. Proof being that Romans did not destroyed their Dacian fortifications prior to their retreat and that they kept a foothold in Dacia till the 3rd century AD. And the Roman Empire offered some level of protection too, partially because of the newly increased Christian connections between the two, partially because they still relied on the Dacian resources, especially gold and salt, a prized commodity.

Roman military insignina and equipment discovered in today Transylvania at Vețel (Hunedoara), at Mintiul Gherlei (Cluj), and at Feisa (Alba) prove that some form of local military organization remained in place even after the Roman retreat.

But the vast majority of Dacians stayed put, predominately in the countryside.

The years of Roman colonization might have changed their language, their religion, their lifestyle, but it wouldn’t have altered their being, their ancestral behavior and connection with their land, its natural cycle. They could go on with their lives, grateful to be left alone. Perhaps they moved away from the big roads, choosing the back-country. Its peace and tranquility. Why would they need the wide, easy access roads since there were no more fairs, no more markets, no more trade? No more monuments to raise, no more inscriptions to commemorate far away kings. No need for coins either, for there was nothing to buy. All that was needed to survive was that what their own two hands could grow. And that’s what they did, they survived the best they could. Free.

Below: bust of Dacian king Decebal, the one who led the Dacians to war against Roman Emperor Trajan (101-102, 105-106AD). A statue of a Dacian warrior, life-size models of Dacian shepherds and a modern-time Romanian shepherd with his cure, woolly do. Notice the continuity of the traditional Romanian attire, especially the hat.

Life went on in Dacian Transylvania after the Roman Withdrawal

Romans had build an impressive Basilica at Ulpia Trajana Sarmizegetusa. Perhaps a century after they left, when life seemed peaceful at last, local Dacian peasants, not finding any practical use to such grand spaces, had made use of them by dividing and creating a few homes within, as the remains of inner walls built with river stone and reinforces with earth, not mortar (as Romans did), shows us today. And the grand amphitheater of Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa was now used as a defense fortress.

Graves around a Roman thermae and dating from the first half of the 4th century AD were discovered at Apulum, today Alba Iulia, Transylvania. Proving perhaps not an urban lifestyle, but a rural continuity of a Dacian lifestyle taking place in Transylvania, as well as in other areas of Dacia, after the Roman withdrawal. And there are also rural settlements where life knew no change whatsoever after Romans left Dacia, much like it happened in Britannia.

If you travel around Romania today, if you’re in a train, speeding past valleys or crawling through mountains, try to erase the villages and to look at the land itself. It is the same land the Dacians occupied, lived and died on. Look at the land and imagine how they would have seen it, where they would have lived, and maybe you will grasp their culture and their lifestyle. And life choices.

Soon after the Romans abandoned Dacia, in the 3rd century AD, the Roman Empire experienced an unprecedented military anarchy. Political instability and building grand establishments, minting more coins, meant the value of the Denar and Sesterț depreciated considerably. They were even made out of less silver, no gold, and even copper. And less of these coins reached the old Dacia (and who would have wanted them now?), none being minted here.

Dacians, including those living in today’s Transylvania, went on with their lifestyle, men working the earth, planting, growing grapes, fruit trees, animals, especially sheep, making tools, mining, going on with their pottery, building homes, while women were weaving, sewing, telling stories, raising children, planting dreams. At the heart of their peaceful world was the hamlet, the village, while the village council was the highest power – just as it’s always been. The home, its animals and immediate belongings were individually owned, while the land, rivers, forests were shared by all. This explains why villages spread over such vast expenses (and still are). The homes and the immediate land is here, but the forest, share, is there, the vineyard spreads over the hill, the pasture, well, a stone throw away too.

Christianity in Dacia (including Transylvania)

Geto-Dacians had a reputation for profound religiosity and strong belief in the immortality of the soul. On the other hand, the long series of martyrs hailing from the towns along Lower Danube (thus including Dacia) during the 3rdcentury AD is proof that the Christianity had a solid foot-hold in Dacia.

Even before 313 AD, when Constantine the Great issued the Edict of Milan that allowed freedom of worship in the Roman Empire and thus legalized Christianity, we know that there were already Christian Dacians.

In addition to them, between the 2nd Century AD and year 313, prosecuted Christians from the Roman Empire would have also seek refuge in Dacia. And after 313 Christianity flourished in Dacia, in part because it was supported by the Christian Dacian population living south of Danube and in part because Dacia became soon surrounded by centers of Christianity.

Between 350 and 450 AD Bishop Niceta of Remesiana christened extensively north and south of Danube and thus an extensive use of the Latin language was introduced in Dacia – in addition to the Christian Dacians living here and already familiar with the Latin language.

Furthermore, the sycessful campaign of Constantine the Great in 336 in Dacia partially restored the Roman sovereignty, thus protecting and permitting the free propagation of Christianity in the region.

Romanian liturgical language rooted in the Latin language

Today the Romanian ecclesiastic vocabulary still resonates of its its Latin origin: Dumnezeu (Deus, God), cruce (crucis, cross), a boteza (baptizare, to baptize), înger (angelus, angel), păgân (paganus, pagan), creştin (christianus, christian), păcat (peccatum, sin), cimitir (caemeterium, graveyard). Essential life aspects and feelings show their Latin origin too: durere (dolor, pain), viață (vita, life), femeie (femina, woman), fecior (filius, son), fiica (filia, daughter), frate (frater, brother), soră (soror, sister), casă (casa, house) and so many more – an account of the christian beginnings of Romanian people.

Although the most suggestive being the term designating the church itself, biserică in Romanian (ancient form beseareca), deriving from Latin basilica (which entered the Latin vocabulary after 313) and not, as with other European languages, from Greek ekklesia.

Moreover, the term basilica was used in Latin only between the IV and VI centuries. After the 6th century the basilica as a construction type disappeared with the meaning we’ve addressed to it thus far, referring in Byzantine Greek only to profane buildings.

It makes sense to conclude that only during the 4th and 6th centuries could the Latin term biserica have entered the Romanian language, as it was only then that Dacians (thus the future Romanians) would have used it to designate both the Christian Church and the church as a building. And the term biserica stuck in this Christian population that spoke a Latin language.

Therefore, we can conclude that the Latin language used by Dacians was the result of a tight weave between local Dacian speech (more on this later) and vulgar Latin introduced by Roman colonists, adopted by the local families they created here during the 160 years of Roman occupation and reinforced with the Latin used by the wave of Christianity washing over Dacia during the 3rd and the 4th century AD.

These were peaceful times before the Hunic invasions of 376 and allowing for the continuations of the Romanisation process up here in Transylvania and acros most of the old Dacia (today Romania).

Archaeological proofs of Romanian Christianity and continuity in Transylvania after 2nd century AD

In Micia, where a Roman fort used to be (today Veţel, Hunedoara county, Transylvania) two grave stones dating from the 2nd century AD were discovered. This is one of them, depicting a family with two children:

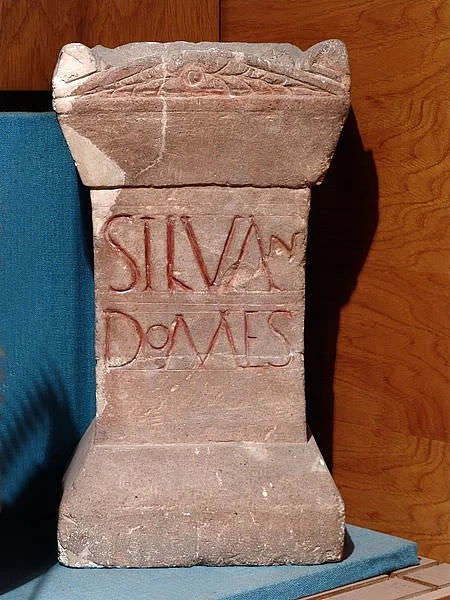

More archeological findings dating from centuries II – IV AD have been unearthed around today’s Transylvania, in Potaissa (today Turda, Cluj county), in Alba-Iulia, the famous bronze from Biertan, Sibiu, with its Latin inscription ‘Ego. Zenovius, votum posui‘ (translating to ‘I Zenovius, do swear’ or ‘I, Zenovius, offered this gift’).

Christian symbols crafted or etched on pottery have also been unearthed, dating from 3rd century AD (vessels with symbols in the form of crosses, carved or scratched); vessels with the symbol of Jesus Christ (the Chrismon symbol), cut after burning, thus showing they’ve been created at a later stage, on a preexisting vessel.

The symbol of Jesus Christ, the Chrismon symbol:

Another inscription depicting Christian motives, this one on a pottery vase and dating from 4th century AD, was discovered at Porolissum (Moigrad, Sălaj county, Tranylvania and Crișana), perhaps surviving a local Christian establishment. Here, clear Christian symbols and inscription were inscribed on the inner side of the vessel: the Chrismon, the dove (the Holly Spirit), the breads, the Life Tree completed with a Christian wish utere felix. Based on the letter types, the character of the writing, and the Christian symbols, the vessel is considered as dating from the middle of the 4th century AD. As is the Christian funeral ritual, the west – east orientation, attested in cemeteries from Apulum (Alba Iulia), Napoca (Cluj), Porolissum (Sălaj), and Potaissa (Turda) – all found in what we know today a Transylvania.

Although dispersed, cores of Christianity did exist in Transylvanian between the II – IV centuries AD and their existence is of high significance if we consider that Dacians lived here in sparse hamlets and village or in forsaken Roman forts. The lack of Christian establishments to this day could be explained by Dacian’s building material of choice at that time, wood. But the archeological proofs that did survived, together with a Romanian vocabulary rooted in Latin and Dacian speech, tell of a perpetual Christian and Dacian existence in Transylvania and around it, wherever Dacians lived, especially after the retreat of the Roman Empire.

NB In this text, although we look at the first four centuries AD, I refer to the intra-carpathian land we know today as Romania’s Transylvania by its modern, Transylvania, although around the times of Roman Dacia it would have been known as Dacia Apulensis and Dacia Porolissensis.

Have you read the beginning, Stories and History of Transylvania, Prehistory to Roman Dacia?

Also o Transylvania‘s history:

Wish I May, Wish I Might, Own Transylvania by Tonight

Stories and History of Transylvania, the Middle Ages

Romanian Transylvania, It’s Origin and Etymology

Sources for Transylvania during the Roman Dacia and until 4th century AD

Constantin C. Giurescu, Dinu C. Giurescu, Istoria românilor din cele mai vechi timpuri şi pînă azi

Floru, Ion S., Istoria Romanilor, Cursul Suoerior de Liceu, 1929

Larousse Encyclopedia of Ancient & Medieval History

Madgearu A., The Significance of the Early Christian Artefacts in Post-Roman Dacia

Nicolae Gudea, Note de arheologie creştină, Some notes on Christian archaeology, source .

Fascinating, Patricia. Toni x

Thank you, Toni 🙂

The music is very peaceful

Yes, it is! I thought so too 🙂