The great halls of Wallachia’s courts echoed with the deep voices of rulers, their boyars and foreign envoys hammering out treaties, forging alliances and, more often than not, deciding the fates of women before they were old enough to understand their worth beyond the ink of a marriage contract. In Moldavia, daughters of noble houses were bartered like fine silks, their marriages securing fragile truces with the Poles, the Hungarians, the upcoming Russians and even Sultans. In Transylvania, a land where Saxon merchants, Székelys warriors and Hungarian lords vied for influence, the Romanians or Vlachs out of the way, noblewomen walked a careful line between tradition and opportunity, sometimes inheriting estates or trading privileges—but always within the confines set by men.

A princess’s hand could seal peace or ignite war. A widow’s silence could be a tactical retreat or a prelude to a sudden, but calculated move. And though few women sat upon the thrones of Wallachia, Moldavia or Transylvania, their influence swiped through the corridors of power like an unseen tide, shaping the fates of realms in ways official records rarely acknowledged.

Beyond the grandeur of Romanian medieval royal courts women wielded power in quieter, yet no less decisive ways. In the bustling markets of Suceava, Sibiu, Brașov, Târgoviște or Bucharest, queen’s hands counted silver and measured bolts of fabric; kicked the flanks of a horse in attack and sieved killing powders with the sole purpose of striking deals that kept their husbands or sons on the throne, their households and fortresses prosperous. Women plotted with like-minded ladies from neighboring lands and ensured their children’s survival when the whims of men left them with little else.

History’s official records may not always sign their names, but these women’s choices left a mark on their world. One strong enough that it is still visible. For behind every ruler was a wife, a daughter or a mother who understood that power is like an embroidery coming alive. It is seldom gifted without work and can only be seized in the spaces between written laws and unspoken expectations.

Medieval Women during War Times

War came often to medieval Wallachia, Moldavia and Transylvania. It did not discriminate. It burned villages, shattered dynasties and turned women’s lives into pawns in a brutal game of survival. When a prince fell from power, his wife and daughters bore the weight of his downfall, cast into exile or forced to barter away their dowries for shelter. In Moldavia, where the constant push and pull of Polish, Hungarian and Ottoman interests made the throne as unsteady as a ship in a storm, noblewomen often found themselves uprooted overnight, left to navigate the dangerous web of shifting alliances. In Transylvania, where noble families balanced on the edge of Saxon, Hungarian, and later Ottoman spheres, war was as much a political maneuver as it was a battlefield. Here, women of status sometimes found themselves imprisoned, ransomed, or even remarried against their will to cement new loyalties.

Raiding forces—be they Ottoman, Tatar, or ruthless Mongols struck deep into the heart of the land, taking captives to be sold into slavery or used as diplomatic bargaining chips. Entire villages vanished overnight, women and children (men too) disappearing into the vast networks of slave trade. Ransoms, when they could be paid, brought some back, but many never returned. Those left behind—widows, mothers, sisters—faced the grim reality of rebuilding. And yet, time and again, women defied the roles set for them. Some took charge of their estates, defending them as best they could in their husbands’ absence. Others orchestrated secret negotiations, bartered for the survival of their families or even led resistance efforts in desperate times.

Foreign travelers, accustomed to their own rigid European customs, saw Romanian women through an exotic lens, their accounts laced with curiosity and contradiction. To some, these women were shackled by patriarchal traditions or cheating husbands; to others, they possessed an unexpected autonomy within their households. The practice of bride kidnapping shocked outsiders, yet the fact that divorce was permitted in some regions set Romanian customs apart from much of Europe. The deep-rooted superstitions and rituals that shaped daily life are also mentioned, while others observed the fluid moral judgments placed on women, often dictated by their dress rather than their actions.

Moldavian women, particularly noted for their fair skin and blue eyes, were described as radiant and full of vitality. Meanwhile, in Transylvania, Romanian women captivated travelers with their natural elegance and distinctive attire. One French explorer remarked:

“Superior to men in their diligence and cheerfulness, they reign as queens in the domestic sphere—an extraordinary fact in this Orient, where even Christian men often view their wives as mere servants. Romanian women, like all Latin women, have an innate sense of elegance and dress with an ingenious coquetry.”

The medieval Romanian women were survivors, adapting to war and political upheaval with resilience that history has too often overlooked. Whether strategists behind the scenes, exiles fighting for their return, or silent witnesses to the rise and fall of rulers, they were far more than mere victims of history—they were its architects in their own right.

Their lives were deeply influenced by male authority, whether in their homes or in exile. However, their resilience—whether as wives, mothers, widows, or rulers—shines through in the records left behind. From foreign travelers to exiled noblewomen, these stories remind us that history is never one-dimensional. The women of medieval Romania navigated a world far more intricate than outsiders often realized.

The Troublesome Laws of Succession to the Throne in Medieval Moldavia and Wallachia

In medieval Moldavia, succession was a volatile and often bloody affair. Unlike Western Europe, where the primogeniture right ensured the eldest son inherited the throne, Moldavia and Wallachia followed a hereditary-elective system. Any male of noble blood, legitimate or illegitimate, son, brother, or cousin, could claim the crown provided he was physically unimpaired. A disfigured ruler was deemed unfit. Women were entirely excluded from rulership, though dynastic legitimacy was often traced through maternal lines.

This lack of a clear succession law fueled endless internal conflicts. Every prince had rivals within his own family, each backed by boyar factions vying for control. Civil wars erupted with alarming regularity, devastating the land and impoverishing its people. Foreign powers, Hungarian, Polish, and the Ottoman Empires, exploited this instability. Claimants to the throne sought external support, offering submission and tribute in exchange for military aid. Often, these powers did not need to invade; ambitious pretenders invited them in.

To counteract this, ruling princes attempted to impose order by designating an heir during their lifetime, usually a son or brother placed in a position of power. Yet the boyars, who held the ultimate power of election, frequently ignored these designations favoring a ruler they could control. The result was a principality that frequently descended into civil war before stability could be restored.

While Western Europe developed centralized monarchies capable of resisting foreign interference, Moldavia and Wallachia remained fragmented. Only under strong and long-reigning rulers like Stephen the Great did the principalities experience stability. More often the throne was won through intrigue, assassination or foreign intervention.

Despite its disastrous consequences no voivode challenged this flawed system, for doing so meant defying the powerful boyar elite who thrived on division. And so, the cycle of instability endured, draining the realm century after century.

Transylvania has known a convoluted history until, during medieval times, it became the richest 2/3 of the Hungarian Kingdom, although it was administered as a distinct unit. Here, the highest-ranking official was the Voivode who was appointed by the Hungarian monarch. The voivodes held extensive administrative, military and judicial powers yet their authority never extended over the entire province. From the 13th century, the Saxon and Székely communities governed themselves within their own “seats,” remaining independent of the Transylvanian voivod. By the 15th century the Voivodeship of Transylvania remained the largest administrative unit within the Hungarian kingdom.

Lady Elisabeth Craven, an English noblewoman, was taken by Princess Măriuca, wife of Prince Mavrogheni. Even in pregnancy, her beauty was undeniable:

“The princess is thirty years old; a truly beautiful woman who resembles the Duchess of Gordon, though her features are softer. Her complexion seemed even fairer, her hair lighter. A bit plump, she is in the sixth month of her eighth pregnancy.”

The Lives of Romanian Noblewomen Through Political and Diplomatic Records

Daring Queens with surprising influences: such notable figures include Doamna (Lady) Clara who fought the political arena of 14th century Wallachia; Princess consort Ruxandra Lăpușneanu who navigated Moldavia’s politics after her husband’s death; Doamna Chiajna of Moldavia or Mircioaica (nicknamed after her husband’s name Mircea) known for her sharp political acumen; Elisabeta Movilă, princess consort of Moldavia, who ensured her family’s survival; Maria Christina, Princess of Transylvania, who saved the Transylvanian throne and Ecaterina of Brandenburg, who also ruled as a Prince in Transylvania, an extraordinary feat for a woman at the time.

Doamna Clara: The Queen, the Cross, and the Lost Crusade, 14th century Wallachia

The winter wind howled through the great halls of Curtea de Argeș, rattling the wooden shutters like restless spirits demanding entry. Doamna Clara drew her heavy mantle closer, staring into the flickering candlelight. She had come to these lands as a stranger, a noblewoman of Hungarian blood, but now she was Voivode Alexander’s wife, bound by marriage to a country that clung to its Orthodox faith like a soldier to his blade.

She had not come alone. The whispers of Rome followed her, carried by papal envoys and letters sealed with the insignia of Saint Peter’s successors. It was her sacred duty, she believed, to bring the true faith to these rugged lands, where monasteries stood like fortresses and where men crossed themselves in the name of an Eastern God. Even now, in the deep of night, monks in dark robes prayed against her influence.

Her husband, Alexander-Nicolae, had entertained her pleas but never yielded to them. He was a warrior, a ruler who had seen too much blood spilled to trouble himself with the wars of the soul. Her stepson, the proud and valiant Vladislav, was more malleable. In him, she saw hope. A bridge between the crowns of Hungary and Wallachia, between the Latin and the Slav. With careful persuasion, she had guided him, until at last, in the year of our Lord 1369, he summoned a Catholic bishop from Transylvania to consecrate churches in the Voivodate.

The news reached Rome swiftly. The Holy Father himself penned a letter, hailing Vladislav as a future champion of Christ, urging him to take the final step—to cast off the Eastern heresy and swear himself to Rome. It was a moment of triumph, a moment that should have cemented her legacy.

But fate had other plans.

A man of quiet resolve and unshakable faith, the monk Nicodim of Tismana whispered his own words into the Voivode’s ear. Warnings of treachery. Of a foreign yoke disguised as salvation. And so, in defiance of Rome and of his stepmother’s counsel, Vladislav turned his back on the Latin cross. Instead of embracing papal rule, he raised an Orthodox Metropolitan Church in Severin, a stone’s throw from the Hungarian border. A warning to those who sought to claim Wallachian souls.

The Pope’s hopes withered and with them, Doamna Clara’s influence. How she must have felt in that moment. Did she rage against the walls of her chamber? Did she kneel before the altar of her own church in Curtea de Argeș, whispering desperate prayers? Or did she merely bow her head, the embers of her ambition turning to cold ash?

Today, what remains of Sân Nicoară is more than just crumbling stone—it is a piece of Wallachia’s soul, standing against the odds, much like the queen who once prayed within its walls.

Ruxandra Lăpușneanu A Voivode’s Wife Who Ruled, 16th cent. Moldavia

Doamna Ruxandra Lăpușneanu, wife of Alexandru Lăpușneanu 39 years her senior, and daughter of Petru Rareș and Elena Brancovici, was born in Suceava in 1538. As the granddaughter of Stephen the Great through her father and of a Serbian despot through her mother, Ruxandra embodied a lineage of power and prestige.

The winter of 1556 brought with it not only the bite of frost but also the promise of power. In the great halls of Moldavia, Ruxandra stood at her husband’s side: Alexandru Lăpușneanu, the voivode of a land forever steeped in blood and intrigue. Though their marriage was forged in politics, whispers of affection crept between the lines of letters he sent from the battlefronts and border towns. From Sibiu and Brașov, he bid merchants procure fruits and rare delicacies, not for himself, but for her.

Yet love, if it had taken root, was no shield against the tide of exile. When Lăpușneanu was cast from his throne, his enemies sharpening their knives, Ruxandra gathered their children and fled. Southward, to the Wallachian court, where her sister, Chiajna, ruled as the voivode’s wife. In the candlelit chambers of princely court of Bucharest. She did not weep, nor did she waver. Instead, she plotted. Envoys rode forth to Constantinople, their saddlebags heavy with gifts, their lips heavier still with words of persuasion. She would not remain the wife of a fallen man. And in November 1563, the gates of Suceava swung open once more to receive its returning prince—with Ruxandra at his side.

But Moldavia’s throne had never been an easy seat. By 1567, sickness laid its cold hands upon Lăpușneanu and Ruxandra, ever a woman of action, called for physicians from Sibiu. The voivode, foreseeing the end, did not clutch at power but instead arranged for their son, Bogdan, to take his place. He would not fight against the tide. Yet even after his passing rumors slithered through the boyars’ halls. After all, many boyars feared him. Like many other voivodes, like Chaijna’s husband Mircea of Wallachia and like Vlad the Impaler, executing a large number of unfaithful boyars was the way of ensuring one’s peaceful ruling.

Had Ruxandra hastened Alexandru Lăpușneanu’s death? The chronicler Grigore Ureche would later claim she had, whispering of poison, of treachery. But the truth? It lay buried with the voivode beneath the stones of Slatina.

At thirty-three, she was a widow, but she was no shadow. The Moldavian throne—her son’s by right—became hers to guard. She did not stand alone. By the account of the monk Azarie, she governed with a steady hand, her mind sharp as any man’s, her rule extending nearly three years. Yet even the strongest fortresses crumble with time.

November 1570 brought her own reckoning. Illness stole upon her in the princely halls of Iași, where she breathed her last at thirty-five. They laid her to rest in Slatina Monastery, beside the man for whom she had fought and schemed. And there, upon the monastery walls, she remains—her votive portrait crowned in precious stones, as if to remind those who pass beneath her gaze: she had been more than a wife, more than a widow.

She had ruled.

Frenchman Edouard Grenier declared that women from Romanian lands were more beautiful than any in Europe, even surpassing those of Paris:

“Every woman was beautiful, even the mothers and grandmothers, for they, too, attended the ball. In their fading features remained a regal grace that made one think—How breathtaking she must have been in her youth! At most, three or four faces were unremarkable—a rarity in Paris.”

Doamna Chiajna – The Fierce Wallachian Voivode’s Wife Who Ruled with an Iron Will, 16th century

The name of Doamna Chiajna echoes through the annals of Wallachian history like the tolling of a great iron bell, bold and unyielding. Laced with the weight of legend. To some, she was the image of ambition and cruelty; to others, she was a woman of her time, navigating the treacherous currents of power as only those with steel in their veins could. The historian Nicolae Iorga lamented how writer Alexandru Odobescu cast her as a villain, shaping her into “a model of audacious wickedness.” I personally adore how contemporary historical fiction writer Simon Antonescu portrayed Chiajna in her epic saga “Chaijna din Casa Mușatinilor”.

Yet the truth, as always, lay somewhere between admiration and accusation.

Born in the proud house of Mușat, daughter of Petru Rareș, the Voivode of Moldavia, granddaughter of Stephen the Great and wed to Mircea Ciobanul, ruler of Wallachia, Chiajna did not inherit a land of peace and plenty, but one where thrones were bought in Constantinople with gold and blood. Her husband’s rule was marked by brute force, a time when boyars fell like wheat before the sickle and the land groaned beneath the weight of endless war and tribute. Yet it was not Mircea, feared though he was, who would carve his name deepest into the stone of history. It was his wife, Doamna Chiajna.

When Mircea Ciobanul was deposed in 1554, the boyars rejoiced, thinking themselves free of his iron grip. But they had not reckoned with Doamna Chiajna. Exile might have broken a lesser woman, but in the great city of the Sultan she moved with the cunning of a chess master. While others whispered in the shadows, she walked the gleaming halls of Topkapı securing allies among the Sultan’s favored wives (especially Roxelena or Hürrem Sultan, legal wife of the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent who was born in an Orthodox family and kidnapped during a Tatar slave raid); or striking bargains in the silk-draped chambers of the harem. She bought her husband’s throne back with a fortune in gold and the promise of loyalty.

When Mircea returned to Wallachia four years later it was with Chiajna’s hand on the reins. He lived but a year more, struck down by a heart attack, a claw to the heart, or poison—none could say for certain. Yet when his body was lowered into the frozen earth Chiajna did not veil her face in mourning. She had no time for tears. Seven children and a country looked to her for protection while a host of enemies sharpened their knives in the shadows.

Her son, Petru cel Tânăr, Petru the Young, was twelve years old when he took his father’s throne. But the true power of Wallachia rested with Mirceoaia, as they now called her. The boyars, bitter from years of oppression, gathered over the mountains, in Transylvania, plotting their return. They did not expect Chiajna to meet them in the field of battle, clad in steel, commanding an army. She led her troops at Românești, Șerbănești, and Boianu, her banner flying high, her voice ringing clear above the clash of swords.

Doamna Chiajna was the first woman in Romanian history to lead an army into battle.

For nearly a decade she ruled in her son’s name, securing Wallachia’s fragile existence through war and diplomacy alike. She arranged strategic marriages, sending one daughter to the court of Poland, another to a noble house in Transylvania and even giving one to the Sultan’s harem; an unbearable sacrifice, yet one that bought her family’s survival.

Power in those days was measured not in years but in heartbeats and in 1568, Petru lost his throne, cast into exile alongside his mother. Banished first to the far reaches of Syria, then to the depths of Asia Minor, their world of courts and crowns faded into the dust of foreign lands. Petru did not live long in exile; whether it was sickness or despair that took him, none could say. But Chiajna endured.

For twenty years more she watched the tides of Wallachia shift from afar, sometimes guiding them in secret, sometimes biding her time. She saw men she had once bested rise and fall, watched as others claimed the throne she had fought for. And when death finally came for her in 1588, it found not a broken woman, not a villain of whispered tales, but a survivor.

The world called her ruthless. They called her monstrous. Yet what man among her rivals could claim to have done less? In a medieval land where thrones were bought with bribes and kept with blood Chiajna was neither saint nor demon. She was simply a woman who refused to be devoured by history.

Elisabeta Movilă, who ensured her family’s survival, 16th-17th cent.

The halls of the princely court in Iași were dimly lit, the candlelight flickering against the high, arched ceilings. The scent of damp stone and aged parchment filled the air, mingling with the ever-present hint of beeswax. Doamna Elisabeta Movilă (1572 – 1617) stood near the great wooden table, its surface covered with letters bearing seals of wax and royal insignias. Each letter carried a promise, a plea, or a threat.

She had never imagined she would rule. Yet here she stood, the widow of a prince, the mother of a dispossessed heir, and the unwavering guardian of the Movilești dynasty. When her husband, Ieremia, had drawn his last breath in the summer of 1606 Elisabeta had known she had no time for mourning. Her eldest son, Constantin, was the rightful ruler of Moldavia but the throne was a perilous seat and family ties were as brittle as old parchment.

Her brother-in-law, Simion, had seized the throne before her son could even don his father’s mantle. Betrayed by the very men who had once bowed before Ieremia, Elisabeta had been forced to flee with her children, unable to so much as mark her husband’s grave. The land of Moldavia, a place she had once walked with the surety of a queen, was now in the grip of another. But she would not yield.

From the safety of Polish lands she plotted, she bargained, she waited. Time was a weapon and she wielded it as deftly as any sword. The Polish nobles, swayed by her cunning and the golden ducats she offered, rallied behind her cause. Her moment came in 1607 when her forces swept back into Iași, driving Simion’s widow, Marghita, and her sons into exile. Constantin, her son, was prince at last but the true power behind the throne was the mother, Elisabeta Movila.

“By the will of God and the strength of my blood, my son shall rule,” she declared and Moldavia, for a time, bent to her will.

She ruled as regent in all but name, a woman in a world where men brandished steel to lay claim to power. But she had no need for swords; her weapons were gold, diplomacy, and an unyielding will. She filled the courts with loyalists, ensured her son’s name echoed in the halls of the Ottoman Porte and, when necessary, sent heavy purses of coin to silence opposition. The boierii (boyars) who questioned her son’s right found their voices stilled by a Sultan more interested in Moldavian gold than Moldavian politics.

But her reign was not uncontested. The previous ruler’s mother, though exiled, wove her own web of intrigue. Time and again she pressed the case of her own sons, appealing to the Ottoman court, whispering in the ears of powerful men that Constantin was a puppet of the Polish crown. Elisabeta fought back in kind, ensuring that Moldavia’s tribute reached Istanbul swiftly, always accompanied by gifts meant to turn suspicion into favor.

Then came the greatest blow. News of Constantin’s death reached her like a dagger in the heart. She had fought for his place, for his right, and now, fate had snatched him away. But she did not crumble. Even in grief, her resolve hardened. A ruler does not yield; a mother does not surrender. She gathered her wealth, her allies, her armies. If one son had fallen, another would rise.

By the summer of 1615 she raised an army of twelve thousand men. At its head rode her noble allies, the powerful Polish rulers. They marched upon Moldavia, upon Iași itself, to unseat Ștefan Tomșa and claim the throne for her second son, Alexandru. On the field of battle near Tătărași, the clash of steel rang through the hills as Tomșa’s forces faltered and fled. Elisabeta’s army pressed on, securing victory, and with it, her son’s place upon the throne.

Fifteen-year-old Alexandru was crowned prince, and once more, Elisabeta Movilă was Doamna of Moldavia.

Yet even in triumph, she knew the shadows of betrayal and ambition loomed ever near. She had won many battles, but power in Moldavia was as fleeting as the morning mist. Still, as she stood beside her son on the steps of the princely court she allowed herself a single moment of satisfaction. She had fought, she had endured. For now, her family still ruled.

Maria Christina, the “ virgin” Princess of Transylvania, 16th cent.

(1574-1621, Princess consort of Transylvania Tenure 13 December 1596 – 23 March 1598, 20 August 1598 – 21 March 1599 Princess of Transylvania Reign 18 April 1598 – 20 August 1598

Maria Christina of Austria entered the world in 1574, a daughter of the formidable House of Habsburg. Raised in the shadow of imperial grandeur, her fate woven into the intricate tapestry of European power. Beauty and intelligence graced her, yet neither could shield her from the cruel tides of fortune. A princess by birth, a queen in name, an exile by decree, hers was a life etched with betrayal and whispered rumors that stretched from the courts of Vienna to the embattled frontiers of Transylvania.

At 19 years old, dawned with a promise of political triumph. Maria Christina’s hand was pledged to Sigismund Báthory, 22, Prince of Transylvania, a union meant to fortify ties between the Habsburgs and the principality against the Ottoman menace. For a month, negotiations twisted through corridors of power, each clause of the marriage contract a calculated maneuver. At last, with vows secured, Maria Christina set forth from Austria, accompanied by her mother and an escort of six thousand German knights.At the princely court in Alba Iulia Sigismund, clad in crimson velvet, awaited his bride with an honor guard and an eight-horse barouche. The wedding, held on August 6, 1595, dazzled with splendor. The bride, pale and regal, wore a sapphire-hued gown, her mantle adorned with gemstones that glittered beneath the candlelight of the great hall. Among the guests stood envoys from Wallachia, Moldavia and the courts of Europe, all bearing witness to what should have been the forging of a powerful alliance.

Yet, behind the ceremonial pomp lay an unsettling truth. On their wedding night, Sigismund did not come to his bride’s chambers. The union, so grand in design, was never consummated. Tongues wagged across Europe. Was the prince stricken by an affliction? Had a jealous hand bewitched him? Darker whispers suggested he suffered from a secret ailment, perhaps the ruinous disease of kings. Others told of an old woman, accused of casting a curse upon him out of spite (namely Margit Majláth, the mother of his rival and executed cousin, Balthasar Báthory. Although Sigismund’s contemporaries made no reference to his relationship with women). Whatever the reason, Maria Christina’s husband rejected her. With that, came political ruin. Within weeks, the prince cast her aside, exiling her to Chioar fortress. Three years she languished there, her rank meaningless, her only companions the damp stone walls and the echo of her unanswered prayers.

Three years later Sigismund abdicated his throne. Tthe tides of fate briefly lifted Maria Christina. Declared Princess Regnant of Transylvania, Wallachia and Moldavia, she signed her name upon official documents with the solemn weight of a ruler: Maria Christierna, Dei gratia Transylvaniae, Moldaviae, Valachiae Transalpinae princeps.

But power, as she had long learned, was an illusion. Emperor Rudolf II, ever wary, dispatched imperial commissioners to Alba Iulia, their presence reducing her to a mere figurehead. By summer’s end, Sigismund had returned to claim what he had so easily abandoned and with him came Maria Christina’s second exile. A brief reconciliation followed, though it bore no more warmth than their wedding vows. It ended as it had begun. With Maria Christina cast aside, forgotten.

The following year she seized her chance to flee Transylvania. She returned to Austria, a disgraced bride, seeking the church’s mercy to annul the farce of her marriage. Pope Clement VIII granted her request in 1607, the grounds: non-consummation. To prove her innocence, she was given a choice: to submit to a medical examination or swear a sacred oath. She chose the latter, preserving her dignity, if not silencing the gossips.

Free of Sigismund, Maria Christina might have faded into the quiet corridors of the Habsburg court. Yet, the tendrils of Transylvanian intrigue reached for her still. While in Austria, she remained in secret correspondence with figures in Alba Iulia and some whisper she became an ally and spy to charming Michael the Brave, Wallachia’s most celebrated warrior-prince.

Michael, a master of battle and diplomacy, had clashed with Sigismund and his kin reshaping the power balance in the region. A curious piece of evidence survives: an allegorical painting from 1601 by Frans Francken, depicting Maria Christina alongside Michael. Was this mere artistic fancy, or a hidden truth? Some claimed admiration had bloomed into something deeper, that she had played a role in the fall of Andrew Báthory, the cousin who briefly ruled Transylvania before meeting his gruesome fate.

One tale, dark with intrigue, tells of a lost El Greco painting portraying Maria Christina and Michael as Herod and Herodias, accepting Andrew Báthory’s severed head as a prize. Whether truth or legend, it speaks of the shadows in which she moved, a woman whose influence had outlived her throne.

By 1608, weary of the schemes of men, Maria Christina sought solace in the Church. She retreated to the Jesuit Haller Convent in Tirol exchanging courtly silks for the habit of devotion. There, far from the betrayals of princes and the whispers of courtiers, she found a measure of peace. In time, she rose to the rank of abbess, wielding a gentler power than that which had once slipped through her grasp.

Maria Christina’s tale is one of contradictions: a Habsburg princess who was once a Transylvanian queen, a bride abandoned yet powerful in her own right. Betrayed, exiled and cast aside, she nonetheless carved her name into history in her own way. Her story remains a moving chapter in the annals of both the Habsburg and Transylvanian courts, a reminder to the resilience of a woman who, though denied love and power, refused to be forgotten.

Ecaterina of Brandenburg, who ruled as a Prince in Transylvania, an extraordinary feat for a woman at the time. 17th cent.

Catherine of Brandenburg was born to rule. Groomed from childhood to stand beside a sovereign, she carried the weight of dynastic ambition as effortlessly as the pearls at her neck. The court chroniclers praised her virtues, describing her as “richly adorned with all the qualities befitting a princely woman.” Though petite, her figure was graceful, her face pleasant, and her lineage unimpeachable. Her sister wore the crown of Sweden, and her cousin that of of Denmark—she was no mere pawn but a queenly piece in the great game of European power.

Her marriage at 24, to Gabriel Bethlen, 46, the indomitable Prince of Transylvania, was not forged in love but in diplomacy. With this bond, Bethlen sought to weave Transylvania into the fabric of Protestant alliances stretching from Denmark to Sweden and the Palatinate.

Yet, Bethlen had orchestrated more than a marriage. He had secured Catherine’s future as his chosen successor. The Transylvanian Diet convened and, before them, Catherine swore her oath as heir. The decision was not theirs alone to make: across the Bosphorus the Ottoman Porte, the other guardians of Transylvania’s fragile sovereignty, lent their approval. Behind this acquiescence lay the deft maneuvering of Bethlen’s allies in England and the Netherlands.

Only three years later, in November 1629 when the cold breath of winter carried Bethlen to his grave, Catherine’s moment arrived. As the widow of a prince and the ruler of his lands she stood at the helm of a nation caught between empires.

But power, though promised, is never easily kept. The forces that had once lifted her faltered when her vision clashed with theirs. She leaned upon her closest advisor, striving to pull Transylvania towards the Holy Roman Emperor, towards Catholic Europe. It was a miscalculation. The nobility murmured, uneasy with her designs, while the Ottomans, ever watchful, reconsidered their favor. Within a year, the tide had turned. She surrendered the throne that had been sworn to her, undone not by battle, but by the quiet erosion of support.

And so, Catherine, who had been groomed to rule, left the land she had governed for but a fleeting season. Once, she had stood before the Diet, a woman crowned by oaths and alliances. Now, she departed, a sovereign unmade, a queen without a throne. She returned to Germany and remarried, living nearly another quarter of a century.

A Foreign Woman’s Perspective on Romania: Ecaterina Salvaresso: a Venetian Woman Who Ruled Wallachiain 16th cent.

Foreign travelers were not the only ones to leave behind accounts of Romanian society; among them were noblewomen who, through fate or marriage, found themselves entangled in the intrigues of the Principalities. One such voice belonged to Ecaterina Salvaresso, a Venetian noblewoman who, for a time, held power as regent of Wallachia while her son, Mihea Turcitul, was too young to rule (1577 – 1583) after his father, Voivode Alexandru II Mircea (great-grandson of Vlad the Impaler), was poisoned. In a bold move, she obtained a firman from Sultan Murad III, granting her the authority to rule. This was an extraordinary feat in an era dominated by male rulers and a testament to her political acumen.

She not only held influence over court affairs but became the sole woman to officially govern the principality. Her political struggles, strategic alliances, and cultural contributions make her a remarkable yet often overlooked ruler in Romanian history.

From the halls of Bucharest fortress she wrote to her sister in Venice, her letters laced with both exasperation and despair. She spoke of a land untamed, of customs that unsettled her refined sensibilities. The Wallachian court, with its blend of Eastern and Western influences, struck her as crude, its traditions at odds with the polished elegance of her homeland. She lamented the “wild” nature of the people, the “unfortunate habits” she observed, and the ever-present weight of what she saw as backwardness. Her correspondence, for all its airs of superiority, reveals more than just an outsider’s discomfort; it grants a glimpse into the struggles of governance, the complexities of Wallachian court life, and the uneasy balance between tradition and change in a land poised between East and West.

Born into an Italian noble family, Ecaterina’s rise to power was deeply entwined with the Ottoman Empire. Her marriage to Alexandru II Mircea, a descendant of Vlad the Impaler, was as much a political arrangement as it was a dynastic union. Given Wallachia’s status as an Ottoman vassal state, her connections to the Porte provided a crucial advantage in securing her husband’s reign and later her own regency.

Her rule was fraught with challenges. The Wallachian boyars, powerful noblemen accustomed to exerting control over the throne, resented her authority. They saw her as both a foreigner and an obstacle to their influence. Political intrigues, rival factions and opposition from within her own court made her reign a continuous struggle for legitimacy.

Despite the political turmoil, Ecaterina left a lasting mark on Wallachian society. She and her husband played a significant role in the establishment of the first printing press in Bucharest in 1573 at Plumbuita Monastery (which is in my childhood’s neighborhood). She also supported the production of religious and educational texts. Her patronage extended to monasteries, most notably the foundation of the Radu Vodă Monastery, close to the royal court, which became a center of learning and faith.

Her political tenure came to an end in 1583 when her son, now of ruling age, was manipulated by boyars and Ottoman influences to push her out of power. Forced into exile, she spent her final years away from the court she had once commanded. She was ultimately buried at the Radu Vodă Monastery, a lasting testament to her contributions.

Ecaterina Salvaresso’s rule challenged gender norms and political conventions. She navigated the delicate balance of Ottoman diplomacy and Wallachian aristocracy, ensuring her family’s survival and leaving an indelible mark on the principality. As one of the few women in Romanian history to wield such power, her legacy is one of resilience, intellect, and quiet defiance against the constraints of her time.

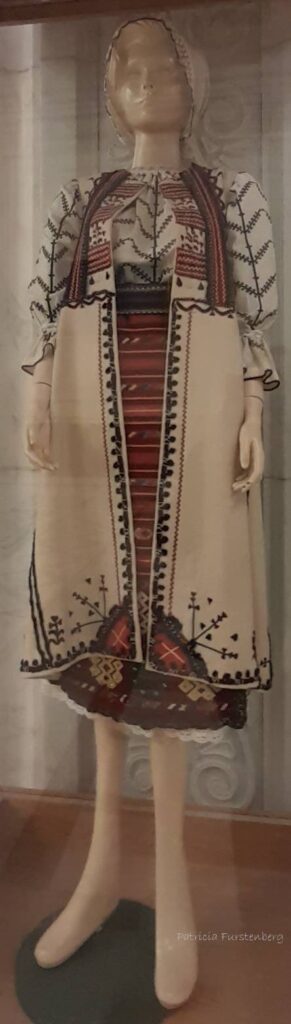

“The women dress almost entirely in the Turkish fashion, wearing long dresses and skirts, and on their heads, they wear very white cotton headscarves that resemble Turkish turbans, which suit them very well. They are women with fair skin, beautiful, and charming in speech.

(Franco Sivori, 1560, private secretary to Petru Cercel, Voivode of Wallachia)

The Life Story of the Romanian Medieval Women was Veiled in Power, Prejudice and Diplomacy

In Wallachia and Moldavia, men’s voices shaped wars and treaties, but power also thrived in patience and quiet defiance. To Transylvanian nobles, Romanians were subjects, their women doubly dismissed. Yet, despite the weight of custom and prejudice, these women endured—not merely surviving but adapting, navigating and, in their personal way, ruling. Beyond the grand halls where rulers bargained for thrones and survival, another kind of power stirred—one not forged in battle but in patience, intelligence, and quiet defiance.

It was a world where a woman’s worth was measured by the roles men assigned her: daughter, wife, mother, widow. She was bound by duty, her fate resting in the hands of fathers and husbands. But reality often outpaced the law. While doctrine dictated submission, daily life demanded something more. And though the church preached of female frailty, the hardships of war, famine, and exile made no such distinctions. Women suffered as men did, bore losses as men did, and, at times, defied fate as men did. Some challenged tradition in ways subtle yet profound—educating their daughters, securing inheritances, bending the rules of a world that sought to confine them.

The medieval Romanian and Transylvanian women were not seen as adversaries to men but as pillars of a structured society. They were the guardians of lineage, the architects of influence behind the throne, the silent negotiators of peace. And though their names are often lost to history, their presence shaped the very world in which we live.

Because “lives can sometimes be led, not just lived.”(Simona Antonescu, “Chiajna din Casa Muşatinilor”) ~”Vieţile uneori pot fi şi conduse, nu numai trăite.”

3 Replies to “Daring Queens and Their Surprising Influences in Medieval Romania”

Comments are closed.