Look past the contemporary photos of Goldsmiths Square Sibiu and discover the life of a medieval village at the time of the Mongol invasion of 1241, through a story.

Do you remember our recent travels? The heart of Sibiu, where the Sxon settlers first set their roots in the 12th century, was composed mainly of Huet Square with its rotonda church, Targului Street (the oldest one of Sibiu), and Goldsmiths’ Square, Piata Aurarilor.

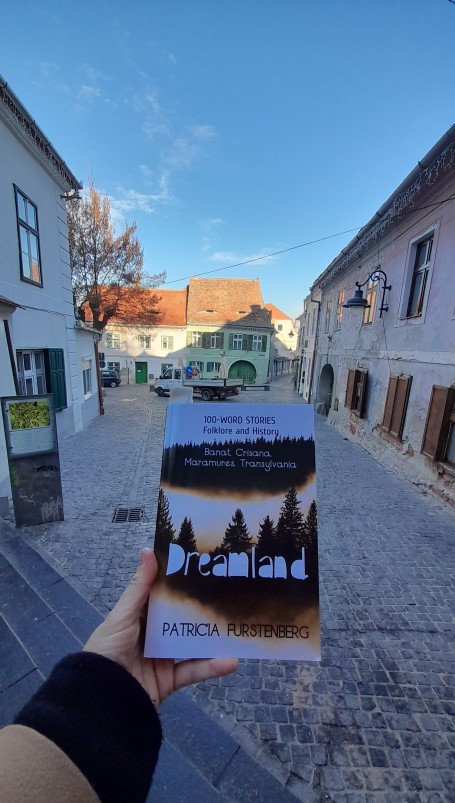

In Goldsmiths Square, Piata Aurarilor, Sibiu, on a sunny December morning, centuries after the Mongol invasion:

Here’s a look at Goldsmiths Square as seen from the end of Targului Street, the view is towards the stairs of Goldsmiths Passage that opens up in Sibiu’s Small Square (going there next time):

Let’s walk through Goldsmiths Square, below. These houses were initially (12th century) built out of wood, with a big gate at the street (that was not a paved one), and big gardens behind, where the home was. While the defense wall (a wooden one too) of these first establishments was here too:

This city that we know today as Sibiu, initially known as the village of Cibin for it was built on the shores of Cibin River, then as Hermannstadt, was one of the furthest, eastern most defense points of Christianity, next to Cârța Abbey for example, during the 12th century.

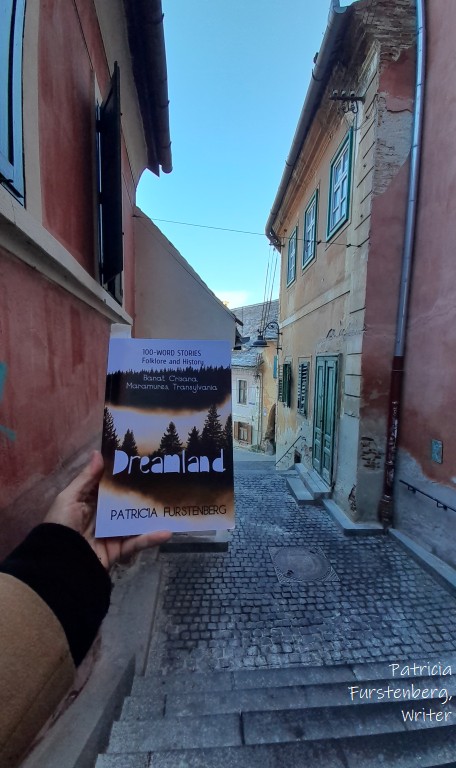

Looking back at Goldsmiths Square (…past my book Dreamland…) from the foot of the stairs of Goldsmiths Passage, we see Targului Street:

Before we head up from the Goldsmiths Square, through the Goldsmiths Passage, to the Goldsmiths Tower and through it into the Small Square of Sibiu, we glance left at this house standing since the 14th century where once a 12th century wooden home would have been, before it was burned to the ground during the Mongol invasion:

Going up, taking the stairs through the Goldsmiths Passage:

If we are to defend this place, be it against the Golden Horde of the 13th century or against the Ottoman troops of the 14th century and later, we are to rush uphill, to the defense tower build and maintained (with men-power and weapons) by the Goldsmiths Guild, the Goldsmiths Tower:

… run, run, up we go!…

After the evil Mongol invasion of the 12th century (story to follow below), when the first wooden defense walls and village of Cibin (then, today Sibiu) was nearly wiped out, a stronger, higher, mightier stone fortification rose in its place known today as the second defense wall (extending further into the quaint Small Square of Sibiu found at the top in the picture above).

Big and small doors along the Goldsmiths Passage, from one landing to the next, as well as the green and alluring entrance to the Architects Union of Sibiu:

The Mongol invasion of 1241, a Story (extract from WIP)

Part 2 – read part 1 here.

Father Nikolaus said they were a punishment sent by heavens.

They came as a stampede. Horses, and of such large size that the day darkened, rising before their riders were even visible. Hooves, digging into flower beds before weapons dug into flesh. Neighing, before war cries covered the yells for help. Strange looking attackers that were faster and swifter atop their horses than any of our men were on foot, even those who’d been to war. One of them intruders, as young as a young boy, jumped one of our sheep when his horse was needed and stirred the frightened animal with such dexterity, that the lamb appeared to be under a spell.

A horde pouring in sheer numbers.

The attackers started marauding, using spears and arrows that whooshed through the air before their swords came thundering down. They seemed to advance on us from all over, pouring from the forest, from behind the same trees that had always surrounded and protected us. As if from behind each trunk, a warrior materialized. In their chaotic attack I see how they try to push us forward; herding us the way dogs herd the sheep. And their net tightens with each stride of the hove, with each blow of sword.

A punishment. Sent by hell.

They throw arrows that carries fire, flames that don’t seem to seize burning. They dip their arrow heads in flasks they carry strapped to their saddles. It smells strong and aromatic in an evil way. Like hell must stink, pulling you in, sickening at the same time. Their arrows start fires that cannot be put out with water, but only smothered with earth.

Our men, armed as they are with swords and mostly household and gardening tools, don’t stand a chance in front of the enemy’s archery.

They force us forward, pushing us, stirring us like we are a herd of lost sheep, which we are, finally locking us between the monastery’s walls.

Then they cheer and retreat. No shame. Their yells of joy die out as the wailing and the cries rise inside the small space. The stampede of hooves that echoed throughout the morning till it echoed inside our heads faded too. They retreat?

We run and gather around Father Nikolaus, fearing for our lives above all, yet none asks who are they?

What is left of us is in the small chapel, our priest urging us to pray and ask for forgiveness.

But the men know better, and soon word spreads like fire, that it is the horde of Batu Khan. The Golden Horde. I wonder if their name comes from the gold tinge they leave behind; of flames that engulfs all that once meant livelihood.

The men soon leave. They leave to protect what is left from the life we’ve just started building here. They leave to fight the Mongols. The women, the elderly and the children remain, secured in their hope, secluded in their faith, locked between the monastery walls.

I look around at the meager supplies we snatched on our retreat here, piled near the fresh water well. I look at the singed faces, at the dirtied clothes, and the crying children. I feel a knot in my stomach and my heart is about to jump out of my chest as I see the big doors, the beautifully carved wooden gates, about to close behind our men. So I grab my mother’s arms and hold a finger over my mouth. I touch the wood that rises all around us to form this beautiful shelter of God, I touch the wooden walls and shake my head, and she understands my fear.

We sneak behind them, before the church walls lock us inside and seal our fate. We sneak behind the men, us two and those who followed us.

The men are to join the makeshift warriors from the nearby village and wait for the Mongols’ return. I pull mother into the forest, where I know a cave wide enough to hide us.

We don’t look over our shoulder. We don’t return. We don’t return to look at what was left from our home, or to see if we could salvage something, anything. Not after a day, nor after two. But some don’t last behind this long. And those, we’ve never seen again.

It is a fortnight when I dare leave our cave, on a night with full moon. I tiptoe through the thicket half wishing that I was wrong. But under the cold light of the moon the raw ruins of a charred monastery tells me the story of how the Mongols returned, after they waited for our villagers to let down their guard, and caught those who dared go out in search of supplies, falling upon them and burning whatever was left from our livelihood.

The charred walls, the torn bodies, the marks of hooves left in the wet soil along Cibin River are silent witnesses of the Mongols return. They tell me how our men couldn’t stand a chance. They show me how the Mongols grounded everything to flames and dust, taking hostages from those who tried to escape the flames.

It is a handful of us who survived with charred ruins of a life that once was full of hopes and dreams. We were a daffodil sending its seeds dancing in the wind, not offering them any support. As I stand on the shore of Cibin River, near the foot of the bridge that took me into the forest so many times, but that also brought the Mongol riders into our life, I see how living within our means will not be enough anymore. Wood did not protect us enough; a stone fortress will be needed.

Copyright © Patricia Furstenberg. All Rights Reserved.

Looking back on history and Goldsmiths Passage one more time before we emerge into the quaint Small Square of Sibiu… next time!

Joining the weekly challenge of Thursday Doors hosted by Dan Antion at No Facilities, where door lovers meet and share unique door photos from around the world! Come see!

A wonderful place filled with history. Thanks for taking me there Patricia 🙂

With great pleasure. I enjoy revisiting holiday photos.

Looking at them I’m almost certain that if we would have waited a little longer, being more quiet and less caught in the moment, we would have hear echoes of past battles.

This was such a delightful read, Patricia. I love history, and I enjoyed the way you wrapped it around your photos. Well done!

✨️

What a history, Pat. I can’t begin to imagine what it would have been like to face those kinds of invasions. The photos bring your story to life. If walls could talk… Thanks for sharing your knowledge!

Indeed, dear Diane. Therefore we should appreciate the present even more.

One of the reasons I love writing historical fiction is to give the past (even as inanimate as a wall) a voice.

Stay well.

Yes, the “good old days” very often weren’t good at all. Lovely square and buildings although I think by the time you ran up all those steps you’d be too tired to defend against anyone! Excellent story as well. I do love historical fiction.

janet

Ah, Lady Janet, yes. Not an easy job defending a fortress, even a small village.

I imagined that running to the top of the stars would give an idea of the sheer amount of energy needed during a battle, when loosing your stamina often meant losing your life.

I appreciate the time you took to read my tale. Thank you.

Oh how I love these shots of an old town!

So glad you do, Teresa ✨️

The plain doors suit the buildings well. You can tell that history whispers from the walls here. (K)

Yes, it does whisper. Lovely said.